| Home | | | About | | | PORTFOLIOS | | | Contact |

BLOG/WRITING

Ch-Ch-Changes

When I began my training to be a visual artist in 1976 the art world was a very different place than it is now. The difference is not in the appearance of visual art itself, in fact it could be argued that not much really novel, conceptually, has been created since the early 20th century. The difference was in the supporting ideology and what art now means to people and especially those in 'the arts'. Few individuals seem to have noticed this, or at least made the effort to comment on the astonishing changes, but I feel compelled to offer some observations from the point of view of a working artist. Observational commentary and philosophy about the visual arts seems to have muted what working artists think, and amplified what those in the domain of educated 'experts' and academics think. I think the point of view of a working artist should also be of significant value, and included in, the overall comprehension of visual art and meaning of an artist and so I'm emboldened to offer some of what I think.

There were periods over 40 years during which I personally didn't feel aware of change; I was too embedded and too preoccupied with working. Developing the skills for the making of visual art and then applying them is an enormous amount of work. I couldn't easily see the forest for the trees. But I'd regularly come up for air and take a look at the topography of the visual arts in general and notice that massive changes were afoot. For example, my old art college was jockeying to become a degree granting institution and bring in art academics and cut loose artist-teachers. In the later half of my working life it became even more apparent to me that the visual arts had in fact changed radically, most particularly for artists. Only working artists my age might be able to make comparisons to what art was like...for an artist...to what it has become. Younger people have only experienced the recent so experiential comparisons of what was and what now is are not possible, nor are the noting of observable changes over the last 50 odd years.

So here's some observations; bear in mind they are conjectural for being anecdotal subjective experiences filtered through memory. But I don't think this subjectivity rules out their value.

-When I went to study art it was more about training. This is not to suggest there was no education in the process, but the most significant thing you could learn was skill. In fact, by learning how to do something you learn a lot about it. If you just learn about something you don't necessarily learn how to do it, and are lacking insight into the actual process. This is a recurring concern of mine regarding drawing; there is a huge difference between knowing 'how to' draw and knowing 'about' drawing, and it is the latter that is severely lacking. If you are studying drawing today, at a university, the first thing you might ask yourself is ' is your professor excellent at actually drawing' and if not what is the basis for their expertise?

-The flagship visual art institutions for study in Canada in 1976 were colleges, not universities and they were difficult to get in to (I have been told about 300 applicants per year would be accepted by my college out of about 3,000). As well there were not a lot of major art colleges. People often went to universities to study art because they couldn't get into a college or because they wanted to study art and receive a steady and relatively lucrative income as a high school art teacher. Some students would leave art college and go to university for academic studies in art and then, with a degree, go to teachers college. I recall it being said at the time, quite cruelly in retrospect but with some degree of truth, 'those who can't, teach'.

-The art world seems to have been colonized by academia in the last 40 years or so. I would venture to say that academia holds an almost complete hegemony over the visual arts, particularly at the institutional level, in my community and country.

-Academia, universities, as an 'organism' or 'entity', don't recognize things that aren't of themselves. They are utterly blind or oblivious to capability, knowledge and skills gained from other locations in society, for example, the workplace ( I have worked for animated film directors who got a job painting animations cels after grade ten and continued working and moving both laterally and upwards in an 'animation factory', doing layout, storyboard, design over the years). Or, self study. Universities only acknowledge the fiat currency of credentials and are blind to commodity currencies such as skill. Increasingly over the years, as the arts technocracy was filled by credentialed individuals, the blindness to the achievements of those from outside the university system has increased. An obvious reason for this is, of course, that by insisting on taking courses, programs and pursuing formal study universities make money and their employees receive relatively high rates of compensation.

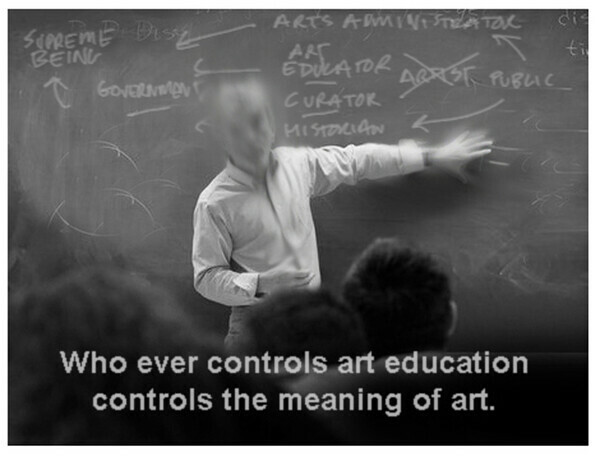

-My instructors in the 70's were generally working artists, or had been. They might work as illustrators, costume designers at the opera, create displays at the museum or science center, and, in the Fine Arts Department where I studied, they would also be exhibiting at commercial and public galleries. Most were teaching part time. The teaching, for working artists, was a relatively well paid gig that could make the difficult and fickle existence of being a working artist a bit more secure, as well as providing the satisfaction of passing on skills to a new generation. In fact, I returned to my art college to instruct drawing and painting for a period of about 5 years whilst exhibiting and working as an art director and background painter for animated films. It still seems sensible to me that occupational artists should teach artists. It seems very different today. The visual arts now seem to be taught largely by a technocratic cadre of full time or aspiring-to-be full time 'regularized' or tenured professional 'art educators'. They are usually not full time working artists and who might never even have tried to earn their crust as an artist; perhaps they do a bit of their own art on weekends or holidays and call it research. This new model actually deprives working artists of potential supplementary income instructing. Furthermore, if whoever teaches art to a new generation defines art for that new generation consider how the meaning of art might change when it is instructed by professional teachers and not working artists.

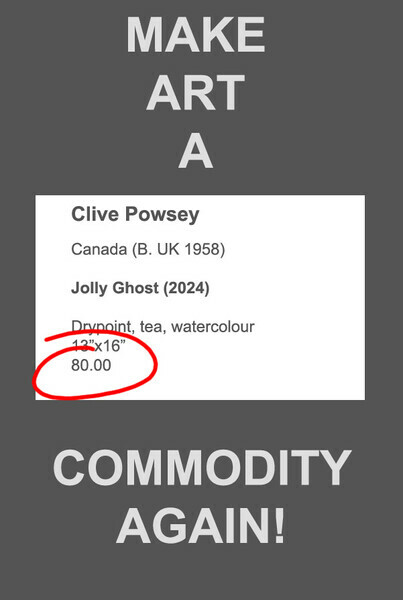

-The 'New Model Artist', the sort of artist who most students probably aspire to be is someone who teaches art full time at a university and is ultimately paid a steady upper middle class salary. They do their art in their spare time similarly to how university professors publish in their spare time. Because of a secure teaching position and salary there is no obligation for their art to be a commodity. So it is easy for art educators to produce non marketable ephemeral art forms such as installations or projections. The institutional public gallery system, also colonized by academia, has fetishized this sort of conceptual art and I often notice in their literature, demean the notion of producing art that can be a commodity. It has been my experience that art educators very often do the same thing.

-Artists are criticized by the technocrats for trying to make a commodity out of the product of their labour...their visual art...but the same criticism is not to be leveled at the technocrats who sell the products of their labour. It is quite all right for technocrats to make a commodity out of their professional services to the arts, their teaching, their arts administration, and their curating. Why should artists be treated differently?

-Some of the 'new' nomenclature in art clearly suggests how art has been defined in recent decades by 'professional' educators. Artists invariably now have a 'practice'...like a lawyer. There is a preoccupation with the word 'research', as with an academic or scientist. Contemporary artists are inter/multi/trans disciplinary; another academic shibboleth. Signalling an academic education is paramount in any artist statement; they 'hold' BFA's, and 'received' MFA's, which, due to educational inflation are becoming a minimum requirement for any self respecting contemporary artist. I have been told my old art college, now a university, won't look at anything below a Phd in hiring an instructor.

-The academic emphasis in arts education has plunged the visual arts into the domain of words, to which images seem to hold an inferior position. This has created a demand for the explicable at the expense of the inexplicable. If an artist (or student) cannot create an image that can be compressed into explicability then they are often considered to have failed. I have often detected in younger spectators of visual art, or film, a sense of...almost outrage really...at not 'getting' what an image or a movie is about. It is almost as though they are being cheated. They fully expect explicable meaning. People who view contemporary are now, generally speaking, 'educated' and they have expectations that they should effortly receive meaning from what they are viewing. It seems inconceivable that they should not understand an image. As someone from the 20th century I feel quite the opposite. I feel that the domain of images is irrational, surreal, and communicates to very different areas of the brain than what can be described in words. I don't expect to necessarily understand images at a logical, rational or conscious level (although of course I try to. Or rather that part of my brain does). I can still happily walk away from an image or film stimulated but perplexed and confused, or 'dumbstruck', but I find this is something that fewer people can tolerate.

-Returning to credentialism; when I was a student the diploma I received, the piece of paper, after four years of art college, wasn't the most important take-away. What was important was demonstrated competency through a portfolio. Your 'bag' was everything. Highly competent drawing was still valued as evidence of having taken the time to study and describe form, something that was considered essential for a visual artist. Drawings might not be the be all and end all of a portfolio but they seemed essential to demonstrate visual competency. If we view the visual arts as an economy, decades ago the strongest currency was the 'commodity currency' of demonstrated competency. This now seems to have been replaced by a fiat currency of paper credentials to indicate their capability. The fact that a dim view is today generally held of skill based commodity currencies such as drawing means it can be almost impossible to determine 'how good' someone is by looking at their work alone. I have piled art images from high school students, undergraduate students and graduate students into files and mixed them up and looked intensely at them individually. In all honesty in many or even most cases I cannot discern, by looking alone, to what level of education an image belongs. Only when I read what is written about the image, or a statement by the artist do I realize the level of education achieved by the author. This is demonstrated, of course, by the use of what are essentially fashionable code words/signals written in an obtuse post modern style by artists who have received a university education.

-There have never been so many people calling themselves artists per square kilometer in human history. Not just astonishing numbers of people who now decide to go to school to study visual art (and this is truly a huge difference between the past and present) but all the millions of people with no training, no idea, who suddenly become self declared artists, perhaps when they retire, for example. Everything is art. Everyone is an artist. This doesn't make everything interesting, it just makes most art boring rubbish.

-The flow of value in the visual arts now seems to be primarily away from artists. The arts are no longer a model where, primarily artists produce art which is consumed by others. Artists now spend vast sums of money on obtaining an education, and then continue to spend considerable sums of money paying for materials, paying to exhibit online or in galleries, join galleries and organizations, and purchase arts services. Juried exhibitions are an astonishing example of this; they have become a business model for fundraising by fleecing artists in the vague/vain hope of exhibiting and receiving exposure. You pay to play, and in return get only the hope that your art will be included in the juried exhibition. The model is really no better than a lottery. Working artists, and as I've suggested there is not shortage of them, have been reduced to consumers. It is the artists themselves who primarily fund and float the arts economy.

-It seems to me there was a time when visual culture was in large part defined by artists themselves. Not completely, of course; academics, aesthetes, collectors and critics all had their input. However, artists had a profound role in the definition of what visual art was because they were valued and their opinions respected. in the past culture transpired from those who produced the artifacts, it was more of a 'bottom up' process, more authentic, more 'self propelled', and the non artist contributors role seemed in large part to describe what was taking place on the ground more than trying to control it. There seems to have been a significant change in this respect. Artists don't seem to be having much of a say in defining art anymore; it's the professional art educators, the curators and arts journalists. If the visual arts is an intellectual economy it is now a kind of Soviet supply side economy that is steered by bureaucrats. Artists themselves are mere interchangeable fodder, Proletariat, in this contemporary regime. I just need to observe how my local public gallery operates to confirm this theory.

-In the past, skilled artists made art. Now, anyone is capable of it. In our local public gallery, people apparently come off the street and are regularly 'engaged' in 'make art' projects. Anyone can make art! Didn't you know? Who needs artists? This engagement is often described as a kind of accessabilty issue, that everyone is open to the 'opportunity' to make art. Or, as an issue of equality; all attempts at art are somehow equal. But why are accessibility and equality demanded for the making of art when it isn't for the curating of art, or the teaching, at universities, of art? Teachers and professors work behind formidable gate-keeping unions and professional organizations and consider their professions exclusive to their kind. How would we feel about anyone off the street flying airliners or performing brain surgery?