BLOG/WRITING

Complex Terrain

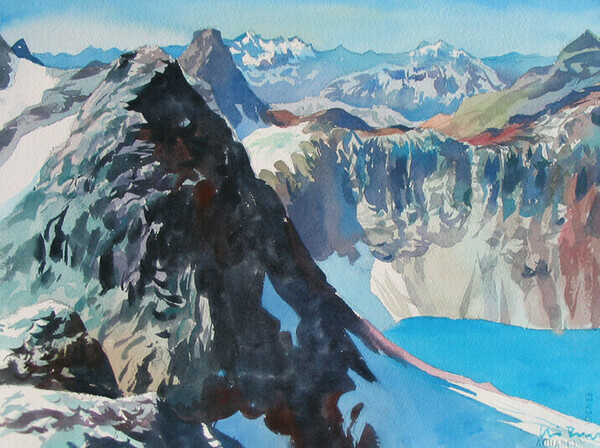

This is an item I wrote for volume 5 of The Comox Valley Collective magazine. I also provided some examples of paintings I made at locations within a days walk of urban centers in the Comox Valley. The notion behind it was to try and communicate how you could turn your back on human development in the Comox Valley and within a day of walking (no driving!) into the hills find yourself in sublime, complex and intimidating mountain wilderness. For this version I've added some of the art I've referred to in the text. Rereading the item, which was heavily edited I've edited a bit more text.

Strike inwards on foot from Vancouver Island’s inhabited perimeter and, in a few hours walk beyond the strip malls, residential neighborhoods, industrial subdivisions, gravel pits, logging slash and spindly second growth trees, you will arrive in largely untouched terrain that swallows you whole. The horizon is higher before you than behind you. Beyond that horizon lie incalculable complexities of terrain: peaks, glaciers, crevasses, snowfields, ice fields, basalt capped with limestone, sink holes and fissures, ravines, frozen lakes, dense forests, rising vapour and plummeting precipitation. These are the elements of Romantic nineteenth century landscape painting, a visual art form so potent at the time that it elevated landscape—within the old hierarchy of genres—far above the pet and livestock paintings to which it had formerly been relegated, eclipsing portraiture and even historical painting in cultural significance. The Romantic landscape became valued for attempting to portray an unspeakable and sublime beauty.

An avalanche in The Alps by Phillip James de Lotherburg

There is an inherent risk to bearing witness to the landscape. The greater your proximity to the overwhelmingly sublime, the greater the risk to your sense of self. It is difficult to discern where the critical threshold is, the point of no return. Caspar David Friedrich’s painting, ‘The Wanderer,’ explores this relationship. In it, a figure stands contrapposto, on the edge, facing the void. It is the posture of a mountaineer on a precipice, a perfectly engineered stance for confronting the inexplicable—weight firmly on one leg, stable for the moment, the other leg hanging loose and bent. Is the figure going to risk another step forward or swing the bent leg backward to safer ground?

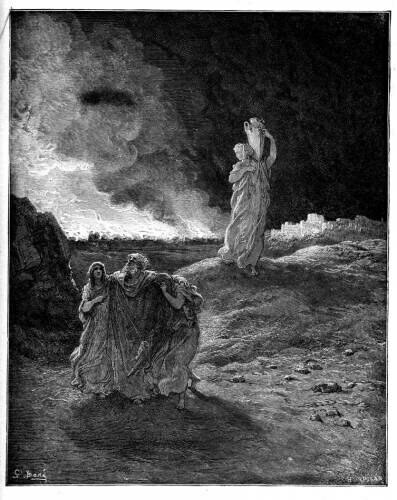

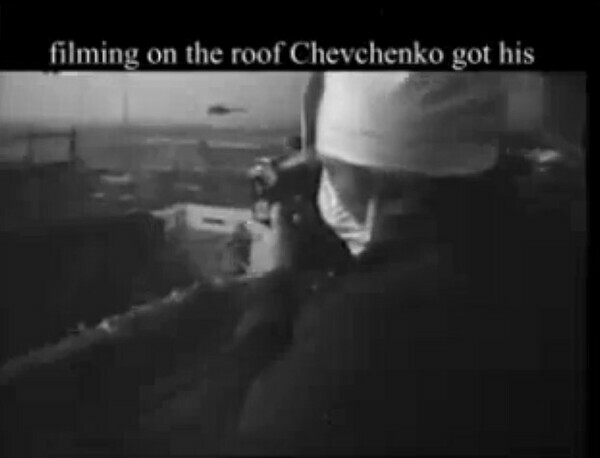

How hard not to look squarely into the face of God and suffer the consequences. How understandable Icarus’s giddy, fatal enthusiasm, Lot’s wife’s fateful glance at Gomorrah, or a photographer’s irresistible, lethal urge to look over a shielding concrete parapet into the devastated reactor core of Chernobyl.

Lot's wife looks back in a print by Gustave Dore.

Chevchenko receives a lethal dose from looking.

Upon return, the wanderer, the mountaineer, the psychonaut, if they survive, is changed. The day-to-day world is seen with new eyes. It can now be seen as complex and fraught with risks to be assessed, that had previously been taken for granted. With the abyss of the past behind and an opaque incalculable future in front, fresh insight excites daily routine. Over the days and weeks, as you begin to take your world for granted again, you will look longingly to the hills on the horizon for your next confrontation with the real.