BLOG/WRITING

In Space No One Can Hear You Scream

This post will be one of several about an approach to introducing the notion of The Elements Of Art to students. As a student myself, many years ago, we were generally taught by full time working artists, not full time art-educators. At the time there weren't really text books for art, and in retrospect there was no clear or monolithic curriculum; the artist-teachers simply taught what they knew about the subject from their work experience in the field. Teaching was more about art and less about pedagogy. I liked this model and look back at it fondly. The instruction at that time was more practical and visceral than theoretical and cerebral. Similarly, when I found myself doing a bit of part time art instruction, I wanted to showcase art concepts in a visceral and practical way. I wanted to try to generate emotional responses to art. I wanted to make art a trigger again.

The urge to trigger was especially prevalent when introducing students to the notion of The Elements of Art; form/shape, texture, colour and space. I didn't want to present these as dry goods. The elements of art can be quiet, nuanced and subtle, but I wanted to demonstrate how powerful an effect on the psyche art images, and how they are structured, can have. As a denizen of the visceral twentieth century art millieu, I wanted to demonstrate that art wasn't necessarily just about pretty pictures or refined theoretical concepts.

I've always been interested in advertising. I think there are strong similarities between art and advertising, and the trajectories of ad careers often pass through a thorough study of art. Art concepts are often evident in advertising, and indeed advertising often refers to the visual arts. I think that the best advertising and art is excellent primarily due to it's exemplary execution; it's art and craft which enhances it's ability to engage at a deep psychological level. Great art (and great literature) and great advertising often seem to deal with hidden irrational emotions, two primary ones which are fear and desire. If I recall correctly, Marshal McLuhan's folklore of industrial man, The Mechanical Bride identified these emotions in adverts. Edward Bernays, who established modern methods of advertising and public relations, has some wonderful folklore surrounding his early twentieth century success promoting the smoking cigarettes by woman for a large corporate client. Apparently after paying a large sum to consult a prominent psychologist he devised a 'Torches of Freedom' campaign, based on the psychologists suggestion that women might subconsciously want to challenge men's power by smoking cigarettes because cigarettes represented a penis. This seems a hilariously alarming suggestion in retrospect, but one that apparently worked. You can view a short clip from Adam Curtis's documentary Century of the Self relating the story HERE.

A still from archival footage shown in The Century of the Self.

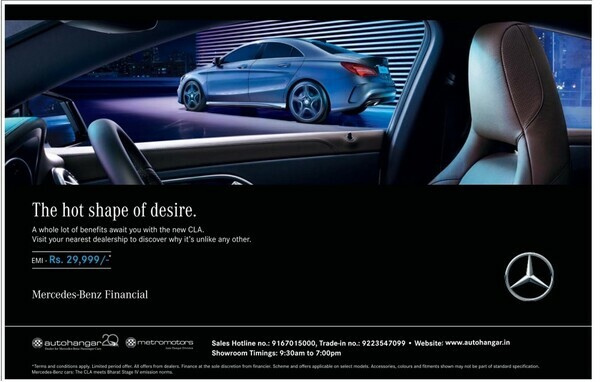

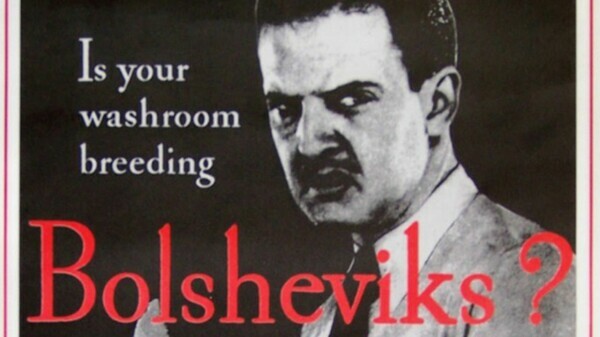

The Torches of Freedom campaign might seem excessive, but there are no shortage of things we fear and desire related to how and why we consume mass produced products. We desire to signal success. We fear emitting unpleasant odors. We desire to look attractive. We fear evidence revealing bodily functions like the discharging of waste fluids or gasses. In some way, almost every advert will pay some kind of attention to our deep seated irrational fears and desires, something great art can also do. Perhaps a significant difference between advertising and art is that we don't pay attention to advertising? We glaze over. But with art we might tend to actively look. Might this be why exposure to advertising has a greater subliminal effect on our unguarded minds? Exposure to art, even if it works on the subconscious, is a deliberate act. Perhaps visual art might sometimes be a creative kind of 'exposure therapy' in which patients are exposed to sources of fear and anxiety that can be experienced in a safer environment? I always enjoyed showing provocative advertising images alongside movie stills alongside great works of art.

Desire in a real advert.

Fear in a parody of advertising from somewhere on the internet.

A metaphor for the slide show that I used to demonstrate the elements of art might be the Voight-Kampff Test used to discern humans from Replicants in the movie Bladerunner. A Voight-Kampff machine is used by a technician who asks test questions and provides scenarios designed to elicit an emotional response in the subject. The machine apparently measures responses by viewing the aperture of the iris of the eye. Artificial humans, or Replicants, have a different response than real humans. Of course, I wasn't trying to test to see if my students were human. I presumed most of them were, and that they would respond appropriately to disturbing depictions of the elements of art. I just wanted to solicit an emotional response from them by showing examples of the elements of art.

Holden administering a Voight-Kampff test to Replicant Leon at Tyrell Corporation's headquarters

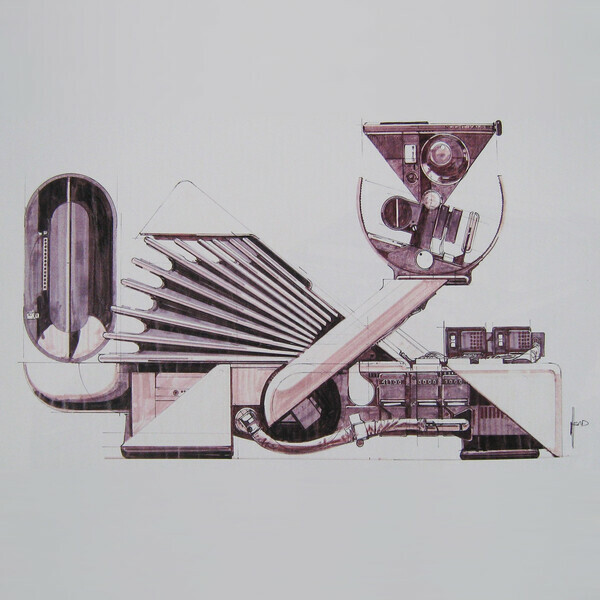

Production design drawing of a Voight-Kampff Machine from the movie Bladerunner.

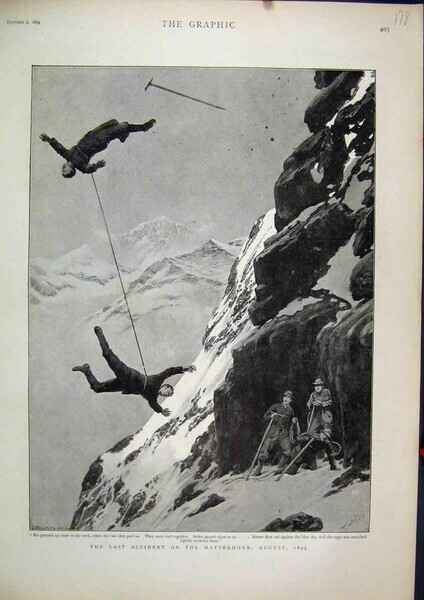

Space is usually supposed as The Final Frontier but I made it the first element of art I'd throw the class into because I find deep space is hard to convey powerfully in 2D projected images in a classroom. So it would be hardest to provoke an emotive response from students. I would therefore work my way through the elements from least to most compelling. Had I the opportunity to put the students on a roller-coaster, or take them to an IMAX film, I might have be able to better impress upon them the power and effect of space. I could of course, mention these sort of experiences and most would share and recollect similar experiences with traces of the original emotions. I explained that I took up rock climbing and mountaineering to experience and hopefully tame my own excessive fearful and agoraphobic response to space. Mountaineers and climbers talk of 'exposure' and how they have to gradually acclimatize themselves to it at the start of the outdoor climbing season. This was what I was attempting to do myself; quite literally a form of self directed 'exposure therapy'. Crags and mountains aren't necessarily a safe environment to experience sources of anxiety and fear, but careful attention to procedures with ropes, harnesses and 'protection' (anchors to prevent a ground fall) create a much safer environment than would otherwise be the case. In time the confidence required for free solo exposed scrambles high in the hills might be achieved.

Exposure to heights and space didn't eliminate my fear and anxiety; for good reason. Fear of falling keeps climbers alive. But the 'exposure therapy' did keep a lid on potentially dangerous fear induced uncontrolled responses. In retrospect I would consider that experiencing the powerful psychological effect of space was a profoundly scaled up and fully immersive variant of perceiving space in a work of visual art.

Of course, there is the other end of the spectrum, also a product of space, or rather lack of it, the claustrophobia of confinement. I'm claustrophobic too ha ha. I can panic when zipped up in a mummy sleeping back when camping, and it requires mental effort to stay calm. I get the same panic response at the back of a crowded bus. Between these two extremes and the the womb and the tomb lie an incalculable number of visceral iterations of psychic responses to space, both large and small, comforting and disturbing. In class we might look at some projected examples of art and identify examples of a sense of space, either abstract or by illusion. Nineteenth century sublime landscapes always provided excellent examples of the illusion of discomforting space.

Monk by the Sea, Caspar David Friedrich

We might look at Cubism, always something of interest to me, in which form invades space and space invades form turning an object, or what remains of it, into a hyperobject. Of course, there is architecture, perhaps the most applied art form for space. A lot of architecture, built at great expense by governments and other powerful organizations, is surely designed as to function as a way to crush the individual, or at the very least make the individual feel very small and insignificant in the presence of some higher order. Think of Cathedrals, for example, whether Byzantine, Romanesque or Gothic.

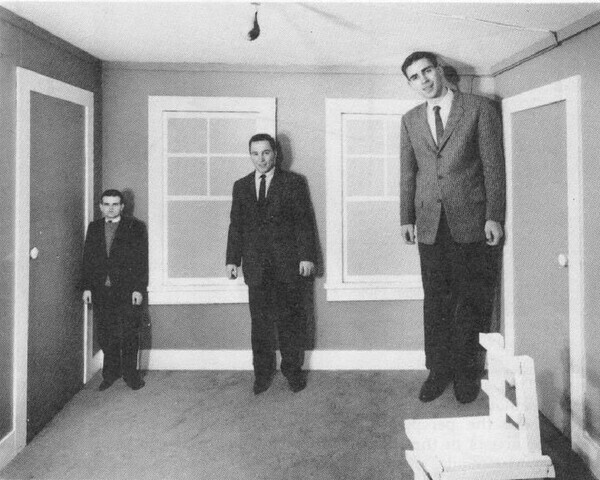

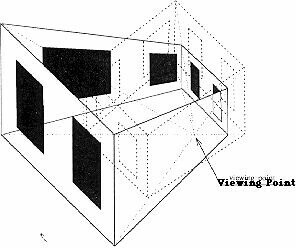

No study of space could not tip the hat to linear and other forms of perspective, and I would usually at least mention 'forced perspective', whereby rather than have, for example, a pathway receding into the back of a yard keeping the same width one might actually make it narrower as it gets further away, thereby 'forcing' the perspective. Another example I would give was an alleged basilica of the Byzantine emperor Justinian which basically did the same thing; audiences would engage at the opposite end of the box-like basilica from where the emperor sat on his Dias, but the architectural 'box' of the basilica actually became smaller toward the emperor's end making him appear larger than life. An extreme example of this is the Ames Room Illusion which was often to be found in fairgrounds.

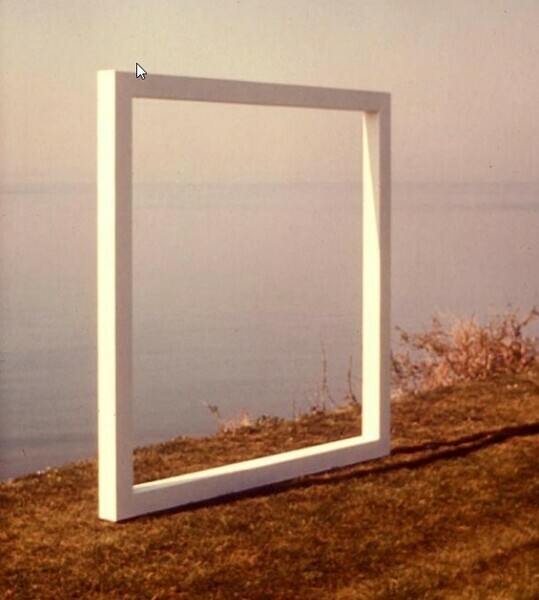

Or we might also look to minimal art of the 60's in which special circumstances could make empty space into something. Within our universe the vacuum of empty space contains energy. The nothingness outside of the universe and existence is another matter; there would not even be space for nothing to exist in.

Ground Outline, sculpture by Peter Kolysnik

After showing examples of space as an element of art I hoped I had elicited some strong psychic responses and always hoped that I had demonstrated that the components of visual art weren't just dry theoretical assumptions but also manifestations of forces that can be used to elicit animal visceral responses from our psychic architecture that has been modeled by evolutionary forces over enormous periods of time.

If, regarding the art element 'space' I had failed in this objective I still had colour, texture and form with which to attack the student's visual sensibilities, and I'll put up posts about these other elements of art in days to come.