BLOG/WRITING

On the Art of Abu Zubaydah

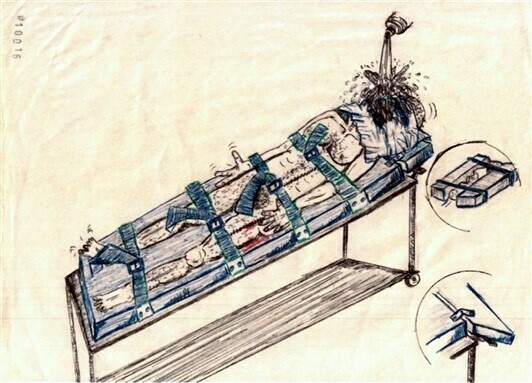

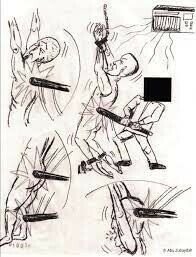

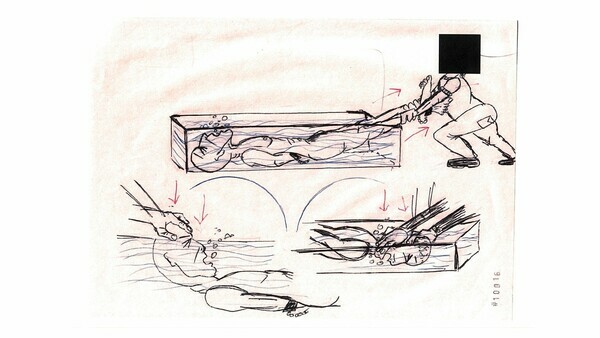

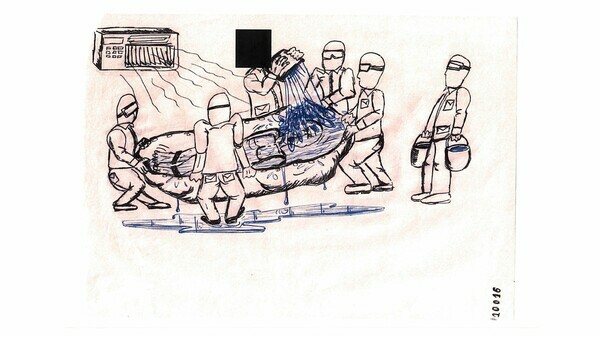

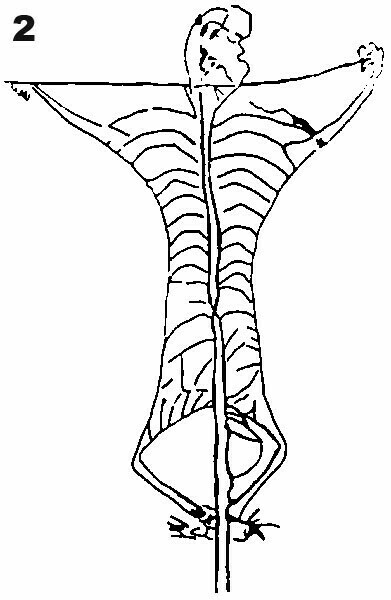

Above, drawings by Abu Zubaydah, depicting his own torture.

Abu Zubaydah has been in and out of the news for many years. I was vaguely familiar with his astonishing story through watching Adam Curtis's documentary Can't Get You Out Of My Head. A few of Zubaydah's naive drawings documenting abuse at the hands of US interrogators at Guantanamo Bay have been previously released and appeared in news items. Recently 40 drawings including new works were published as part of a report called American Torturers by The Center for Policy and Research; for a news item which also includes the full report click here.

This longish post will consist of a series of observations and comparisons of torture and figurative art, relating to the drawings of Zubaydah and the excellence or lack of excellence in drawing. As a visual artist I cherish excellence in drawing skills more than any other visual facility. I can't think of anything more significant to the visual arts than the coherent and skilled describing of form. Drawing is looking...and more...describing...and there is no keener way to observe and visually respond to the world. Observational drawing is connecting the eye, the mind and the hand through the body and there cannot be many more lucid ways to exist as an embodied entity in the world. Drawing, vast amounts of practicing it, (I mean tens of thousands of hours not simply taking a drawing course for a credit or prerequisite), allow an aspiring visual artist to make some sense of substance and matter and accumulate an inventory of mental templates of abstract biomorphic and geometric forms that can be recognized in the the chaos of the observed world or used for spontaneous visualizations. Delineating with rare skill requires hard work, enormous quantities of time and patience, and an enormous amount of enthusiasm to acquire. To have put in the time and effort to learn how to draw with excellence is, for me, an indicator of how seriously a visual artist takes their calling, their vocation. I rarely have time for artists who are too lazy or arrogant to put in the effort to learn and retain the ability to draw well. Similarly I would probably not be interested in reading a book by an author who never bothered to learn how to read, or watch a movie by a filmmaker who had never learned how to use a camera. Abu Zubaydah's drawing skills are dismal and childlike. But I'm going to make a case that Zubaydah's clumsy childish drawings might transcend a threshold between naive illustration and diagrams into 'art' due to his profound experiences.

Torture is appalling. I can't imagine it is in any way a practical method to wrangle information out of anyone. I'm certain I would tell my torturer anything they wanted to hear. The most practical way to obtain useful and accurate information from me, if I even had any, would surely be to park me in a comfortable bar with The Swingle Singers playing, buy me copious amounts of alcohol, strike up a conversation, feign interest in what I have to say, and ask me questions. If this would work for most other people this leaves me with the appalling conclusion that torturers represent an element of society who enjoy cruelty, and are ready and waiting in the wings to spring into action when organizations, government, death squads military or criminal, mistakenly believe their cruel services would be of value. Torture might be as human a quality, for at least part of the population, as compassion.

Perhaps torture's inhumane 'humanity' explains it's presence as a recurring theme both in history and the art historical record. Those records seem relatively flush with depictions of the inflicting of pain and brutal dispatching of people for various reasons; punishment; interrogation; inquisition and even public entertainment, as in events at the Roman Colosseum or medieval public executions. It has to be accepted that a portion of human society must enjoy inflicting pain and suffering on others and a segment of society must derive a sordid pleasure from watching such carnage.

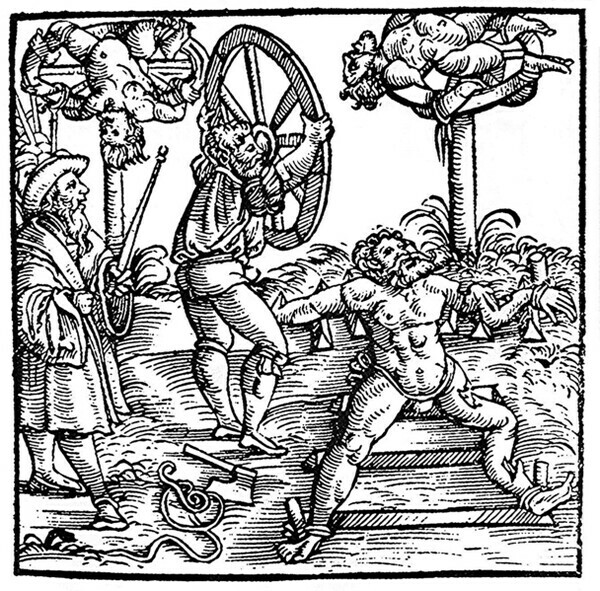

Medieval torture and executions with The Breaking Wheel.

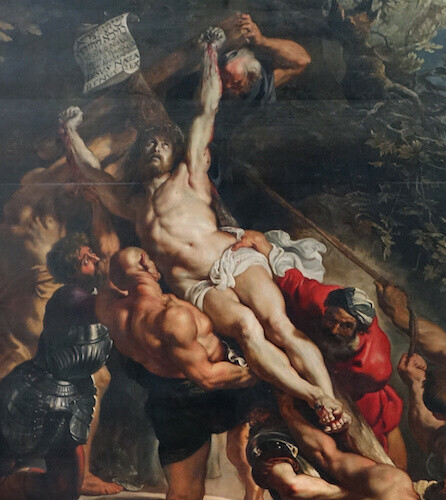

I grew up Catholic so was from an unnervingly young age exposed to a visual record of torment celebrated by The Church from gory crucifixions in the building itself but also in the glossy catechisms I used to browse during the tedium of mass. I recognize to this day the mortal human flesh of the Saviour, saints and martyrs, being inhumanely dispatched in paintings by Rubens and Caravaggio.

A crucifixion by Rubens memorable for me to this day.

As unwholesome as this exposure was, I'm not regretful; my exposure has assisted with appreciation and understanding of a great deal of art. So much of the Western art historical record derives from Christian sacred art and ritual, and before the advent Christianity, from equally bloody sacrificial and slaughterous rites. There is a long lineage of sacrificial myth. Sacrifice, of humans and then animals, has been a creepy fascination for humans over the ages. Julian (The Apostate), the last pagan Roman Emperor, was horrified at upstart Christians hurling themselves at martyrdom like suicidal brain infested zombies, yet on a daily basis he slaughtered quantities of animals for the purpose of divination. There must surely be a link between cruelty to, and the slaughter of, both animals and humans, as we are made of the same stuff.

In a neighbor's garage I once bore witness to the butchering of a bear carcass and painted it.

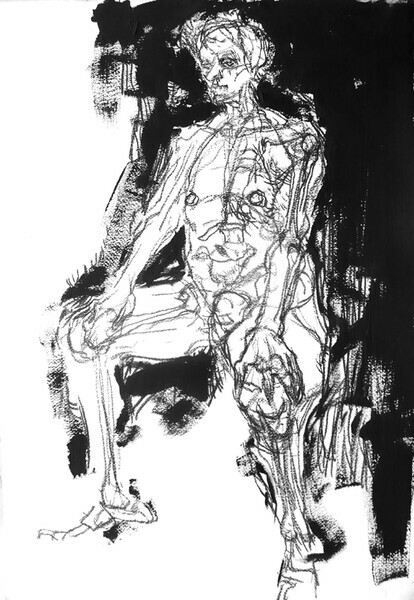

Catholic thinkers like Rene Girard appear to believe human culture was founded on murder and the mechanism of scapegoating and I would not find this unsurprising. At the very least my Catholic exposure sensitized me to the mortality of the flesh and the body's frailty to disease, damage and dismemberment. I consider a lot of art in the figurative tradition, both sacred and secular, to be about embodiment...and disembodiment. I've spent vast amounts of time as an artist observational drawing from the disrobed human form; life drawing. It often occurs to me that many of the souls whose mortal flesh and bodies I have drawn and studied so intensely are now dead. There's a paradox in humans revering the nude and torturers stripping their victims naked. The clue might be in 'naked' vs. 'nude'. I can't draw from life without realizing that before me is a mortal human like myself, born to die. My mirror neurons are presumably stimulated. It is always my hope that this somehow comes through in my drawings in some small way. But when we strip someone naked something completely different seems to happen; the naked are vulnerable to abuse, reduced to animals, less than human; as depicted perhaps in medieval and Renaissance scenes of hell and judgement in churches.

A figure drawing of my own.

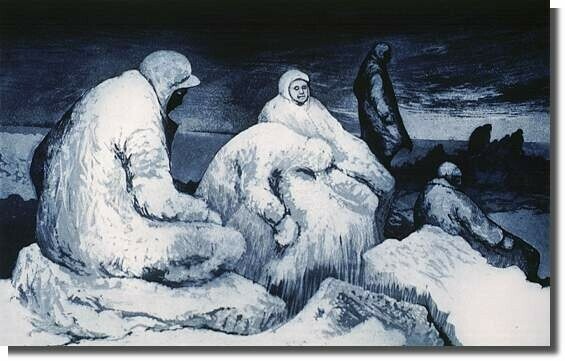

When instructing students figure drawing I often tried to bring attention to the notion of creating groups of figures. We have an ingrained evolutionary fixation, I suspect, to be deeply interested in interacting groups of people. We're social primates who form interacting troupes and are deeply interested in what clusters of our kind are doing. All the crucifixions and flagellations and portrayals of Biblical events are essentially groups of interacting humans. I recall the early prints of artist David Blackwood, who for a couple of decades worked on 'The Lost Party' series of etchings based on a weather related sealing disaster off the Newfoundland coast in 1914. An erudite person I knew claimed that if Blackwood found the lost party he'd be out of a job. The exceptional series of prints was ostensibly about 'The Lost Party', and that Canadian-content historical attribution surely contributed to Blackwood's success. But, content aside, at a deeper abstract level, it seems to be intriguing arrangements of human figures in a sublime and desolate location that may be most transfixing. Not the content. Not to take away from the poignancy of Abu Zubaydah's bearing witness, this might also be true of what he is also presenting, beyond content, beyond message, and beyond documentation; groups of hominids interacting in fixating, unusual, indeed profoundly disturbing ways. Zubaydah's drawings have this in common with the greatest examples of figurative art.

A print from The Lost Party

Zubaydah's drawings are naive to say the least. At best they are junior high school level. Jean Piaget documented predictable phases of children's drawing from scribbling, to circles, to cephalopodic figures with crude appendages, to full frontal figures, and finally, attempts to express action, dimension, perspective and proportion. Zubaydah's drawings seem to be on a par with the final predictable phase of children's drawing, generally that of a child about 10. Piaget claimed estimates of age and IQ could be made fairly reliably from perceived complexity. Every child draws and progresses in skills until, at an almost predictable age, around ten, most stop drawing. Those few who continue to draw used to be the sort that went on to attempt to be artists. After children become youths the predictable succession of development as described by Piaget for young children ends and it becomes difficult to estimate age or IQ beyond that threshold; factors such as training, social distractions, hormones, sports, schooling, opportunity and aptitude come into play. Zubaydah's drawing facility seems on the cusp of the transition from childish drawing to that of adolescent youth, the final predictable phase of childhood visual development. Zubaydah might have an awareness of comic book presentation, and it's not inconceivable that he was aware of the visual arts. He might, for example, have seen of the profound, timely but disturbing figurative paintings of Leon Golub. Regardless, there is a perceived authenticity to Zubaydah's drawing which is not wholly derivative.

Leon Golub's envisioning of an interrogation

Authenticity is a huge concern for me; I've always tried to be honest with myself and with my art and have no doubt abjectly failed. There are degrees of authenticity which I suspect the best any artist can do is aspire to. Authenticity is not to be confused with novelty. There are wheels within wheels though; I consider Andy Warhol incredibly unauthentic, something he worked hard to achieve, which sort of makes him incredibly authentic in his honest and forthright un-authenticity. Does that make sense?

Back to drawing, there is a risk for an artist that, as skills accumulate, authenticity diminishes. This doesn't have to happen, of course. An artist doesn't have to merely create clever drawings if they can delineate with rare skill. But it's easy to fall into the flourishes of clever slickness. In observational drawing it is easy to stop looking. I often confessed envy to and for my beginner drawing students as I instructed them in observational drawing, measuring angles and proportions, creating pictorial depth and perspective. I saw them struggling to focus and observe intensely, draw adequately and the results were drawings that, if slightly naive and riddled with corrective errors, are nevertheless stunningly authentic and moving to look at. The corrections, the pentimento, document the struggle to will form and structure to emerge from line work on a page, and this seems to create an recognizable authentic aesthetic. Their searching line is to be savored.

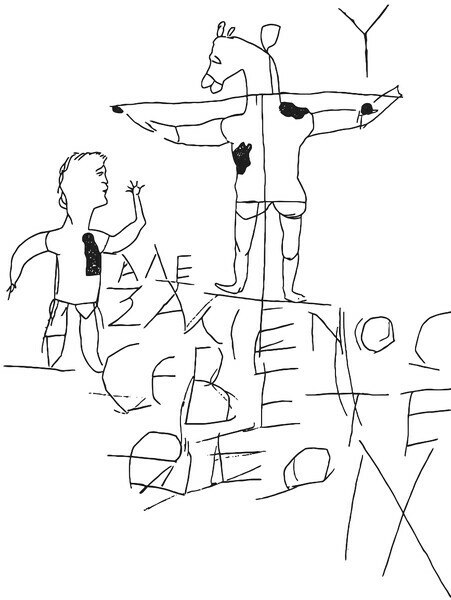

Here, below, even more primitive than an observational art student drawing, is a rubbing of a second century naive unskilled inscribed graffito on stone depicting a crucifixion for comparison with the Rubens above. The carnal, almost animal nature of the crude drawing is compelling to my eye.

For further comparison, below is a rubbing of a graffito of a crucifixion from around the same time which may or may not be one of the very earliest depictions of Christ's crucifixion. The inscription says 'Alexamenos worships his God' so the object of the drawing is something of a 'cartoon' mocking Christians and Christianity. That might be Alexamenos with the asses head on the cross 'worshiping his God' through crucifixion and being mocked by a passerby, or it might be Christ himself being crucified with Alexamenos as the observer 'worshiping' his God. Either way the asses head is the biggest clue to the intent of the drawing.

Compelling drawing is usually achieved (for me) by an enormous amount of looking and and executing, and at least ten thousand hours of practice (according to lore). But sometimes I suspect, circumstances, experience, emotional response (and sometimes coincidence) allow for an aggregation of qualities that make someone unskilled (child, adult prisoner, adult mental patient...) take an excruciatingly painful shortcut to exceptional visual art. Here's an anecdote to try and demonstrate this. I was once teaching a summer outdoor sketching and painting class through the very college I had attended. There were serious students, looking to learn and receive credits in the hope of getting occupations in art, but also dabblers. One such older dabble had very little ability, drawing skills of about a ten year old. My task at best would be to provide her with an interesting three weeks of self actualizing entertainment and perhaps coax her to improve skills without devastating her confidence. She was sitting drawing on a stump, drawing another student sitting on a stump with Lake Ontario and a chaotic arrangement of sailboats in behind. The drawing was dreadful but the figure, the arrangement and the chaotic array of sails struck me as haunting. The hairs on the back of my head went up. 'Good God' I exclaimed, 'It looks like there's been some kind of terrible accident!'. Out of the corner of my eye the woman slumped over and and burst into tears. It transpired that her son had committed suicide two weeks before the start of class and she'd almost not shown up. 'My God; that is all in the drawing' I said. I would consider her drawing one of the most profound images/works of art I've encountered first hand; up there with Pontormo's Deposition. It gives me the shivers to relate this story to this day. For me it's the emotional and painful human circumstance of the drawing's genesis that made it compelling and pushed it across a boundary between a naive scribble and into art. Similarly, I suggest, with Zubaydah's drawing. I don't think that unskilled drawing is usually capable of becoming art, except in astonishing instances like these.

More on authenticity. You know when illustrators (or artists) try and make something very contrived look loose, compulsive and sketchy? As if it were just dashed off? How fake it looks? The illustrators sketchy look is 'affected'. I could recognize this falsity even as a child. Those sketchy scribbles surrounding an illustrated form didn't look authentic; they didn't look like the kind of genuine pentimento you see around a Renaissance drawing study, where the artist is feeling out the form stroke by stroke and finally recognizing a true contour to fortify. You can see the work, the effort in the authentic drawing. The skilled illustrator or artist contrives a mere flourish. I admired my drawing students struggling to deploy drawing methods and techniques; their errors, alterations and efforts were genuinely observable in their drawing. They weren't faking it. Zubaydah's drawing skills seem inadequate in the face of the horrors inflicted on him but through sheer will and effort he manages to cobble together a rudimentary but compelling documentary vision of his abuse.

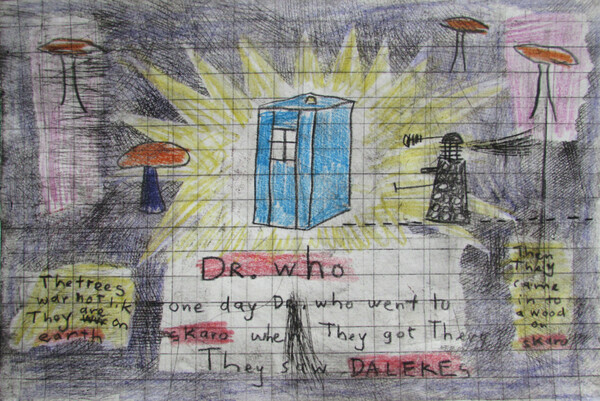

I have on a number of occasions tried to channel my former selves into my art, including my childhood self, and this has included actually using old drawings, teachers admonitions and attempting childish drawing as an adult. I didn't have anything particularly dramatic to communicate from my childhood, except the effect of television, which entranced me at the time, and in creating a series of child-like prints/drawings I perhaps hoped the results, if banal, might at least be an authentic representation of something or other...perhaps the dramatic effect on childhood of television. Like so many quests for an authentic vision, if my outcome lacked authenticity I at least hope the effort didn't. I also hope this particular anecdote provides some background to my fascination with the notion of naive unskilled drawing and complex skilled drawing. It is as though if you are extremely interested in good drawing you must also have a reciprocal interest in bad drawing. You can't comprehend up without down, nor sweet without sour.

A chine colle drypoint print and drawing I made from my childhood Dr. Who drawings.

Let's consider one another comparison to Zubaydah beyond children's drawing; the art of the insane. John M. MacGregor was an invited art history instructor/lecturer at the College I attended, and he taught a course on the art of the insane whilst writing his book on the subject, which appears to be the first, if not one of the first comprehensive tomes on the subject. Our college was structured on an arts and crafts model; working artists and artisans taught prospective artists and artisans. There were drawing and painting studios, printmaking studios, illustration departments, a textiles department, a modest film and animation department, an 'experimental arts' department, and a foundry. It was very hands on. Academic or Liberal Arts courses were provided and they seemed intended to provide background and general knowledge for working artists rather than create serious academics. There were the standard 'Survey's of Western Art', which often amounted to slide shows but there were also some more unusual courses, for example, on early Christian and Medieval art, and, MacGregor's course on the art of the insane. I didn't actually take MacGregors course, regrettably; you just couldn't cover everything and working with your hands to acquire skill is extremely time consuming, but a number of years after college I was teaching there and had chats with MacGregor at the photocopier. I got hold of his book which is relevant for anyone who is an artist of 20th century vintage or interested in the era. 'The Discovery of the Art of the Insane' shows just that, how the discovery of the work of mad persons had a profound effect on the work of 20th century artists. MacGregor points out, if I recall correctly, a considerable amount of the art world and artist's interest was Romantic in nature and plagiarist. MacGregor parses out notions surrounding the perceived feverish raw mad unskilled talent of individuals in mental institutions and provides a clearer vision of how and why compelling works of 'art' were created by the insane. For example, consider how difficult it is in this day and age in Canada to be a productive artist. Madmen and madwomen, confined to institutions where they were fed, clothed, housed, with time on their hands were sometimes encouraged to draw and paint for therapeutic reasons and furthermore received positive feedback for doing so by staff who were genuinely interested in documenting and understanding their afflictions. They were given a space to create which is much more difficult to find in the outside world. MacGregor also shows that many mad artists were actually artists on the outside prior to incarceration, and those who weren't, and had no training whatsoever, were given the time and space to develop and unleash their naively executed fixations. Child-like skill could, as with the incarcerated Zubaydah, be focused in the production of detailed imagery with a disturbing and compelling point of view. The art of the insane, indeed psychology and psychotherapy, nevertheless deeply effected 20th century artists from Surrealists to Expressionists to Art Brut, Outsider Art, and even Stuckism. MacGregor provides examples of what is close to copying the work of mental patients by Man Ray and Jean Dubuffet, and by looking at art by artists I often notice similarities myself.

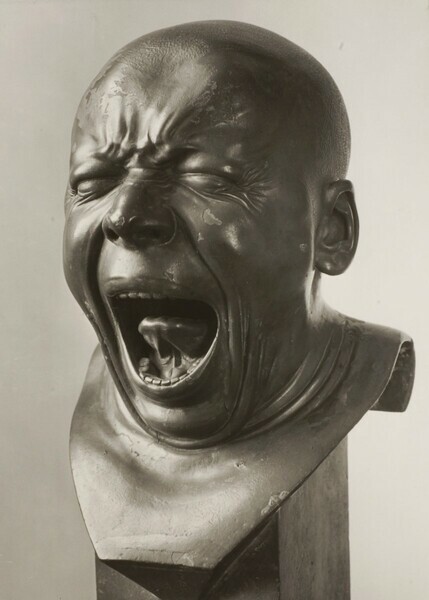

A sculpture by accomplished 18th century sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt who was afflicted with paranoia and hallucinations.

Canadian sculptor Mark Prent.

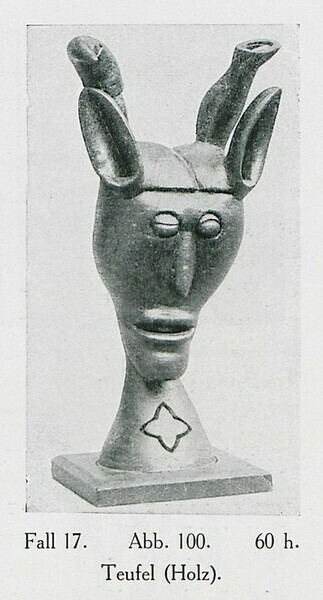

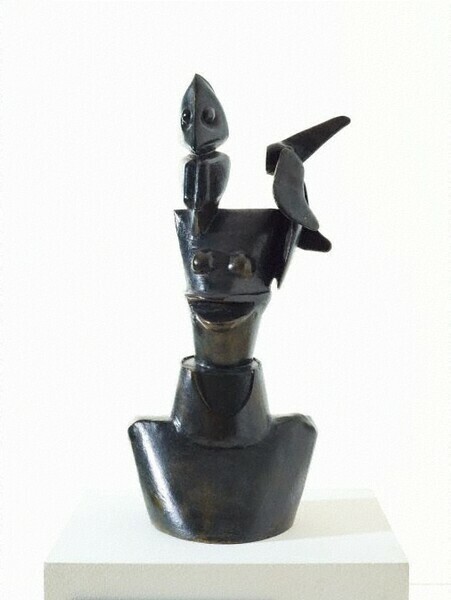

A sculpture by mental patient Karl Brendel in the collection of the Prinzhorn Collection, 'Devil', and a sculpture by Max Ernst 'The Imbecile'.

I believe Abu Zubaydah's appalling experiences may mainline his art into a place of special consideration. As an artist I like to pay close attention to an image's visceral artistic qualities. There are historical and contextual considerations to Zubaydah's drawing which are beyond my expertise, but as an artist I'm drawn to his work for aesthetic reasons and would without doubt make a point of seeing an exhibition of his drawings in a not dissimilar way that I would a skilled and well known artist of note. Zubaydah's drawings will exist in the historical and, I hope, the art historical record along with other great images of human manufacture from the past and future.

As a final note, more sinned against than sinner, one hopes very much Zubaydah is released and is provided compensation for his torment and finds a modicum of peace in what time remains for him. As well, one hopes that the criminality of 'extraordinary rendition' and accompanying torture and abuse will one day be recognized more widely and in court.