BLOG/WRITING

In Space No One Can Hear You Scream

This post will be one of several about an approach to introducing the notion of The Elements Of Art to students. As a student myself, many years ago, we were generally taught by full time working artists, not full time art-educators. At the time there weren't really text books for art, and in retrospect there was no clear or monolithic curriculum; the artist-teachers simply taught what they knew about the subject from their work experience in the field. Teaching was more about art and less about pedagogy. I liked this model and look back at it fondly. The instruction at that time was more practical and visceral than theoretical and cerebral. Similarly, when I found myself doing a bit of part time art instruction, I wanted to showcase art concepts in a visceral and practical way. I wanted to try to generate emotional responses to art. I wanted to make art a trigger again.

The urge to trigger was especially prevalent when introducing students to the notion of The Elements of Art; form/shape, texture, colour and space. I didn't want to present these as dry goods. The elements of art can be quiet, nuanced and subtle, but I wanted to demonstrate how powerful an effect on the psyche art images, and how they are structured, can have. As a denizen of the visceral twentieth century art millieu, I wanted to demonstrate that art wasn't necessarily just about pretty pictures or refined theoretical concepts.

I've always been interested in advertising. I think there are strong similarities between art and advertising, and the trajectories of ad careers often pass through a thorough study of art. Art concepts are often evident in advertising, and indeed advertising often refers to the visual arts. I think that the best advertising and art is excellent primarily due to it's exemplary execution; it's art and craft which enhances it's ability to engage at a deep psychological level. Great art (and great literature) and great advertising often seem to deal with hidden irrational emotions, two primary ones which are fear and desire. If I recall correctly, Marshal McLuhan's folklore of industrial man, The Mechanical Bride identified these emotions in adverts. Edward Bernays, who established modern methods of advertising and public relations, has some wonderful folklore surrounding his early twentieth century success promoting the smoking cigarettes by woman for a large corporate client. Apparently after paying a large sum to consult a prominent psychologist he devised a 'Torches of Freedom' campaign, based on the psychologists suggestion that women might subconsciously want to challenge men's power by smoking cigarettes because cigarettes represented a penis. This seems a hilariously alarming suggestion in retrospect, but one that apparently worked. You can view a short clip from Adam Curtis's documentary Century of the Self relating the story HERE.

A still from archival footage shown in The Century of the Self.

The Torches of Freedom campaign might seem excessive, but there are no shortage of things we fear and desire related to how and why we consume mass produced products. We desire to signal success. We fear emitting unpleasant odors. We desire to look attractive. We fear evidence revealing bodily functions like the discharging of waste fluids or gasses. In some way, almost every advert will pay some kind of attention to our deep seated irrational fears and desires, something great art can also do. Perhaps a significant difference between advertising and art is that we don't pay attention to advertising? We glaze over. But with art we might tend to actively look. Might this be why exposure to advertising has a greater subliminal effect on our unguarded minds? Exposure to art, even if it works on the subconscious, is a deliberate act. Perhaps visual art might sometimes be a creative kind of 'exposure therapy' in which patients are exposed to sources of fear and anxiety that can be experienced in a safer environment? I always enjoyed showing provocative advertising images alongside movie stills alongside great works of art.

Desire in a real advert.

Fear in a parody of advertising from somewhere on the internet.

A metaphor for the slide show that I used to demonstrate the elements of art might be the Voight-Kampff Test used to discern humans from Replicants in the movie Bladerunner. A Voight-Kampff machine is used by a technician who asks test questions and provides scenarios designed to elicit an emotional response in the subject. The machine apparently measures responses by viewing the aperture of the iris of the eye. Artificial humans, or Replicants, have a different response than real humans. Of course, I wasn't trying to test to see if my students were human. I presumed most of them were, and that they would respond appropriately to disturbing depictions of the elements of art. I just wanted to solicit an emotional response from them by showing examples of the elements of art.

Holden administering a Voight-Kampff test to Replicant Leon at Tyrell Corporation's headquarters

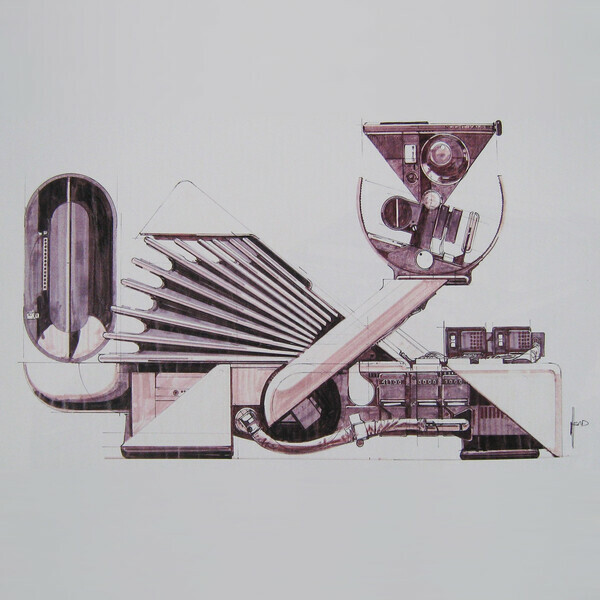

Production design drawing of a Voight-Kampff Machine from the movie Bladerunner.

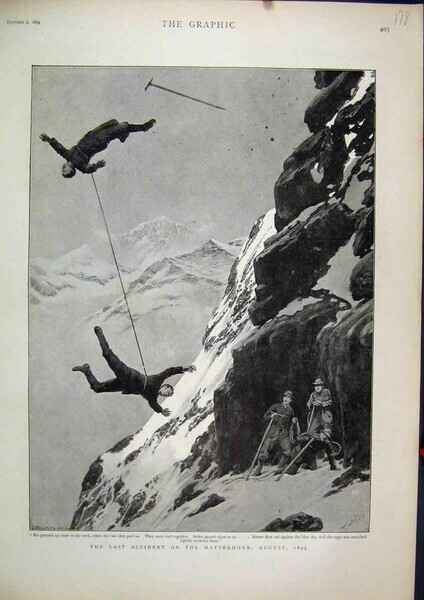

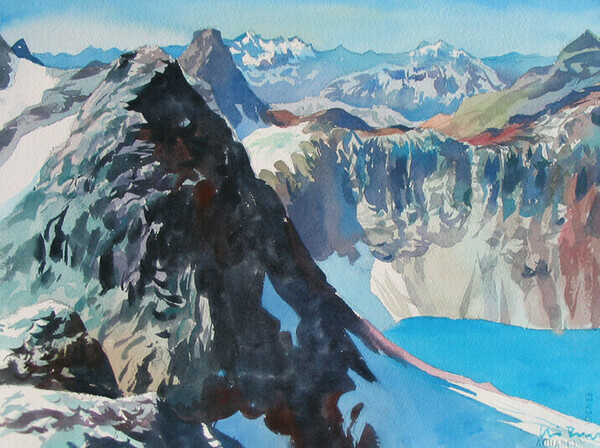

Space is usually supposed as The Final Frontier but I made it the first element of art I'd throw the class into because I find deep space is hard to convey powerfully in 2D projected images in a classroom. So it would be hardest to provoke an emotive response from students. I would therefore work my way through the elements from least to most compelling. Had I the opportunity to put the students on a roller-coaster, or take them to an IMAX film, I might have be able to better impress upon them the power and effect of space. I could of course, mention these sort of experiences and most would share and recollect similar experiences with traces of the original emotions. I explained that I took up rock climbing and mountaineering to experience and hopefully tame my own excessive fearful and agoraphobic response to space. Mountaineers and climbers talk of 'exposure' and how they have to gradually acclimatize themselves to it at the start of the outdoor climbing season. This was what I was attempting to do myself; quite literally a form of self directed 'exposure therapy'. Crags and mountains aren't necessarily a safe environment to experience sources of anxiety and fear, but careful attention to procedures with ropes, harnesses and 'protection' (anchors to prevent a ground fall) create a much safer environment than would otherwise be the case. In time the confidence required for free solo exposed scrambles high in the hills might be achieved.

Exposure to heights and space didn't eliminate my fear and anxiety; for good reason. Fear of falling keeps climbers alive. But the 'exposure therapy' did keep a lid on potentially dangerous fear induced uncontrolled responses. In retrospect I would consider that experiencing the powerful psychological effect of space was a profoundly scaled up and fully immersive variant of perceiving space in a work of visual art.

Of course, there is the other end of the spectrum, also a product of space, or rather lack of it, the claustrophobia of confinement. I'm claustrophobic too ha ha. I can panic when zipped up in a mummy sleeping back when camping, and it requires mental effort to stay calm. I get the same panic response at the back of a crowded bus. Between these two extremes and the the womb and the tomb lie an incalculable number of visceral iterations of psychic responses to space, both large and small, comforting and disturbing. In class we might look at some projected examples of art and identify examples of a sense of space, either abstract or by illusion. Nineteenth century sublime landscapes always provided excellent examples of the illusion of discomforting space.

Monk by the Sea, Caspar David Friedrich

We might look at Cubism, always something of interest to me, in which form invades space and space invades form turning an object, or what remains of it, into a hyperobject. Of course, there is architecture, perhaps the most applied art form for space. A lot of architecture, built at great expense by governments and other powerful organizations, is surely designed as to function as a way to crush the individual, or at the very least make the individual feel very small and insignificant in the presence of some higher order. Think of Cathedrals, for example, whether Byzantine, Romanesque or Gothic.

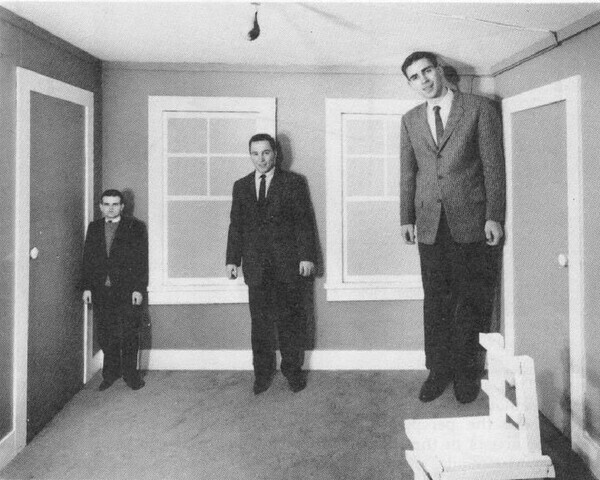

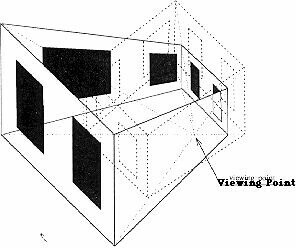

No study of space could not tip the hat to linear and other forms of perspective, and I would usually at least mention 'forced perspective', whereby rather than have, for example, a pathway receding into the back of a yard keeping the same width one might actually make it narrower as it gets further away, thereby 'forcing' the perspective. Another example I would give was an alleged basilica of the Byzantine emperor Justinian which basically did the same thing; audiences would engage at the opposite end of the box-like basilica from where the emperor sat on his Dias, but the architectural 'box' of the basilica actually became smaller toward the emperor's end making him appear larger than life. An extreme example of this is the Ames Room Illusion which was often to be found in fairgrounds.

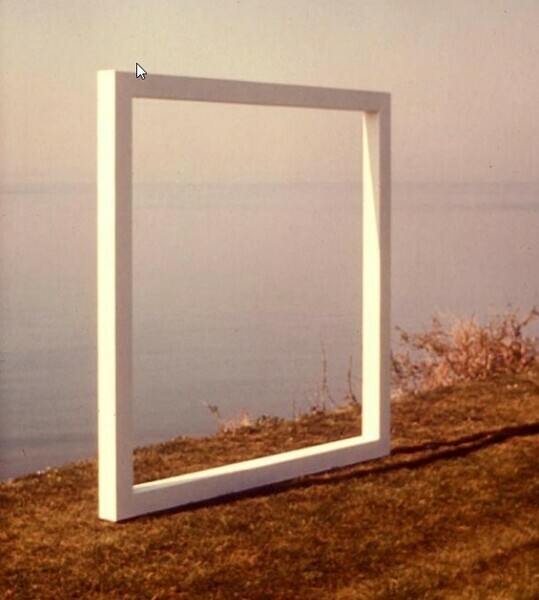

Or we might also look to minimal art of the 60's in which special circumstances could make empty space into something. Within our universe the vacuum of empty space contains energy. The nothingness outside of the universe and existence is another matter; there would not even be space for nothing to exist in.

Ground Outline, sculpture by Peter Kolysnik

After showing examples of space as an element of art I hoped I had elicited some strong psychic responses and always hoped that I had demonstrated that the components of visual art weren't just dry theoretical assumptions but also manifestations of forces that can be used to elicit animal visceral responses from our psychic architecture that has been modeled by evolutionary forces over enormous periods of time.

If, regarding the art element 'space' I had failed in this objective I still had colour, texture and form with which to attack the student's visual sensibilities, and I'll put up posts about these other elements of art in days to come.

Roadside Art-Picnic

A cover of Roadside Picnic appearing to depict an artifact called a 'Full Empty'.

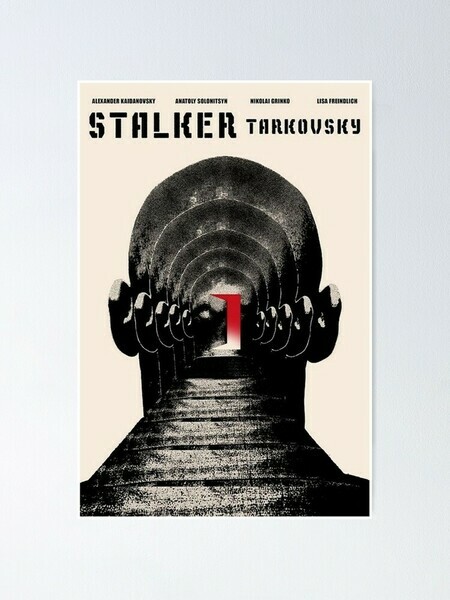

In 1973 the Soviet Russian science fiction novel Roadside Picnic, by brothers Arkady and Boris Strugatsky was published. The movie Stalker by Andrei Tarkovsky was based on the novel. In the novel, aliens have very briefly visited Earth; passed through as much as passed by. The locations of contact, called 'Zones' have been littered with technologically advanced incomprehensible artifacts with mysterious and often dangerous qualities. The original use for the objects is not known. So-called 'Stalkers' take risks to enter The Zone and retrieve artifacts abandoned by the aliens. They then sell them. Scientists access the artifacts and experiment with them at great risk of catastrophic results but occasionally with wondrous outcomes; a kind of gambling where they are sometimes able to find applied uses, for example as energy sources or as medical interventions. The novel title is a metaphor, outlined by the character Dr. Valentine Pillman. It is as though aliens have pulled over at the side of a highway and they...'light fires, pitch tents, turn on the music. In the morning they leave. The animals, birds, and insects that watched in horror through the long night creep out from their hiding places. And what do they see? Old spark plugs and old filters strewn around... Rags, burnt-out bulbs, and a monkey wrench left behind... And of course, the usual mess—apple cores, candy wrappers, charred remains of the campfire, cans, bottles, somebody’s handkerchief, somebody’s penknife, torn newspapers, coins, faded flowers picked in another meadow.' None of the litter left behind makes any sense to the resident life forms.

The Roadside Picnic is a wonderful metaphor for the imagined existence of technologically advanced alien artifacts, but it also seems an excellent one for visual art and images. We have no idea why we make visual art (certainly I don't), and very little knowledge of the inner 'space' (vs. outer space) from which it comes. Traditionally Muses (aliens of a sort) delivered inspiration as ineffable as the artifacts in the novel, and the Muse could be dangerous and destructive to the person possessed by them. During my formation as a visual artist the notion of an artist at risk of damage by inspiration still existed and could be witnessed, often in my drug and alcohol savaged art instructors. It was as though the artistic process was destructive of the individual seized by inspiration, as though knowledge and vision was an 'information hazard'. Indeed art itself could be viewed as dangerous. Twentieth century artists seem to regularly plunge to Nihilist depths of depression, alcohol and drug addiction. Danger and risk seemed to be a byproduct of the art occupation and even the powers of observed art itself, not unlike the observed objects in 'The Zone'.

Art objects and images had and perhaps still have great power. We find uses for them such as to sell products in advertising, hang on walls to fill space, put on plinths, not fully knowing where their inspiration comes from or why they function as they do. Sometimes it is their sheer uselessness that makes art objects so mesmerizing; art for arts sake. This is not so unlike the artifacts from The Zone in the novel; the 'So-so's', 'Shimmers', 'Jolly Ghost's', 'Empties', 'Rattling Napkins', and 'Lobster Eyes' observed and retrieved by Stalkers.

As a denizen of the mid to late 20th century when Roadside Picnic was written I readily accept that visual art, including film making should not be explicable. I relish the ineffable and irrational nature and mysteriousness of visual art and images, of how they can communicate mutely, without 'saying something'. I can still leave a movie or an art exhibition with no clear understanding of what it was about and be grateful to have simply experienced exquisite craftsmanship and feel stimulated to have glimpsed some meaning or even truth, as through a glass darkly. In ages past those Muses who delivered inspiration were aliens of sorts. Our own minds seem like aliens. We have no clear idea how our minds work, transmit insights or have powers. More and more research psychology and neuroscience suggests that we are not as self aware and conscious as we delude ourselves into believing, and that our tiny slivers of awareness simply rationalize what we do unconsciously and automatically. I have no clear idea what I've been doing for 40 years as an artist and I'm not sure I actually want to, because I believe it would be counter productive magic notions and ineffabilities still attached visual art.

I have no idea of what I'm trying to communicate in this post.

After a usual frantic life humans lead I'm now in my final years. Despite being convinced for most of my working life I knew what I was doing I now realize I have no clear idea what my persistent creation of drawn, painted and printed images was for or about. I was like a stalker in The Zone fetching imagery from aliens installed in my subconscious. The quality of the loot was unpredictable, sometimes an applied use could be found for it, sometimes it was useless or even dangerous. Roadside Picnic, The Zone and Stalkers might be useful metaphors not just for art but for life itself, and the life of the artist.

A poster for Tarkovsky's Stalker movie.

Complex Terrain

This is an item I wrote for volume 5 of The Comox Valley Collective magazine. I also provided some examples of paintings I made at locations within a days walk of urban centers in the Comox Valley. The notion behind it was to try and communicate how you could turn your back on human development in the Comox Valley and within a day of walking (no driving!) into the hills find yourself in sublime, complex and intimidating mountain wilderness. For this version I've added some of the art I've referred to in the text. Rereading the item, which was heavily edited I've edited a bit more text.

Strike inwards on foot from Vancouver Island’s inhabited perimeter and, in a few hours walk beyond the strip malls, residential neighborhoods, industrial subdivisions, gravel pits, logging slash and spindly second growth trees, you will arrive in largely untouched terrain that swallows you whole. The horizon is higher before you than behind you. Beyond that horizon lie incalculable complexities of terrain: peaks, glaciers, crevasses, snowfields, ice fields, basalt capped with limestone, sink holes and fissures, ravines, frozen lakes, dense forests, rising vapour and plummeting precipitation. These are the elements of Romantic nineteenth century landscape painting, a visual art form so potent at the time that it elevated landscape—within the old hierarchy of genres—far above the pet and livestock paintings to which it had formerly been relegated, eclipsing portraiture and even historical painting in cultural significance. The Romantic landscape became valued for attempting to portray an unspeakable and sublime beauty.

An avalanche in The Alps by Phillip James de Lotherburg

There is an inherent risk to bearing witness to the landscape. The greater your proximity to the overwhelmingly sublime, the greater the risk to your sense of self. It is difficult to discern where the critical threshold is, the point of no return. Caspar David Friedrich’s painting, ‘The Wanderer,’ explores this relationship. In it, a figure stands contrapposto, on the edge, facing the void. It is the posture of a mountaineer on a precipice, a perfectly engineered stance for confronting the inexplicable—weight firmly on one leg, stable for the moment, the other leg hanging loose and bent. Is the figure going to risk another step forward or swing the bent leg backward to safer ground?

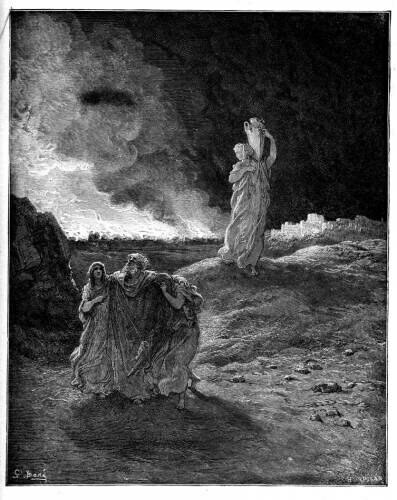

How hard not to look squarely into the face of God and suffer the consequences. How understandable Icarus’s giddy, fatal enthusiasm, Lot’s wife’s fateful glance at Gomorrah, or a photographer’s irresistible, lethal urge to look over a shielding concrete parapet into the devastated reactor core of Chernobyl.

Lot's wife looks back in a print by Gustave Dore.

Chevchenko receives a lethal dose from looking.

Upon return, the wanderer, the mountaineer, the psychonaut, if they survive, is changed. The day-to-day world is seen with new eyes. It can now be seen as complex and fraught with risks to be assessed, that had previously been taken for granted. With the abyss of the past behind and an opaque incalculable future in front, fresh insight excites daily routine. Over the days and weeks, as you begin to take your world for granted again, you will look longingly to the hills on the horizon for your next confrontation with the real.

A Brush With Virtual Unreality

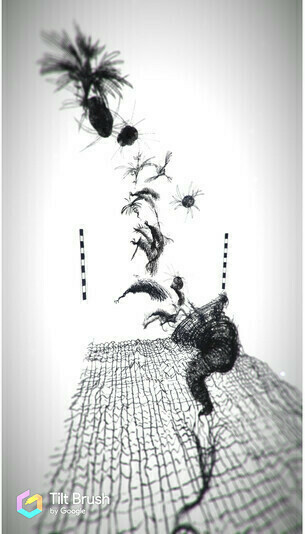

A screen grab of one of my VR drawings.

Some years back, around 2018, I was invited to take part in a 'research project' at the local public art gallery to use Google Tiltbrush virtual reality at a local VR arcade. Several years later, after experimenting with novel text-to-image AI I find myself reflecting on disturbing (for me) aspects of the VR experience, of technology in general. I spent many hours down at the VR 'arcade' experimenting with drawing. Participating artists weren't paid for their work, but received 300 dollars I believe it was, for 'engaging the public' at an art opening for 'Constant Change' at the gallery. As a working artist, I insisted that my 'actual' work, which was printmaking, also be included in the exhibition alongside the virtual. As well I suggested the other artists be able to do the same. As well as the AI artists, in the main gallery a MFA graduate had an exhibition which consisted of perimeter wall painting of what might be large pixels suggesting a digital environment and in the middle of the gallery a circle of electrical cords with a vacuum cleaner robot operating with a dog bowl on top. The artist wept during her art talk. As well children were exhibiting in the gallery under the title of 'Calling All Robots'. These were young students in a robotics program. All artists gave a short talk which was printed. No one seemed to have any great concern about the technology. Here's my talk which I've edited in a bit of what I took out for brevity.

As someone trained in and deeply committed to a skill of the eye, mind and hand (drawing) I'm probably more suspicious than most of the benefits of excessive technology. I've nevertheless been curious enough to casually follow developments of the last few decades in both 3D modelling and more recently 'virtual' drawing and painting. So it was a fortunate and welcome opportunity to experiment briefly with VR drawing thanks to Matt Adamson of VRSpaces and the CVAG. I was pleased that curators Denise Lawson and Angela Somerset have seen fit to show examples of not just the virtual work of the artists involved in this project, but also their actual work.

Seeing and drawing in 3 dimensions was a novel experience, but not overwhelmingly so. VR did not open up a new psychic domain because drawing, whether 2D or 3D, is describing form and/or shape with points, lines and planes, so the shift from 2D to 3D was fairly seamless. Conceptually and even practically Tiltbrush drawing is not much different than drawing with pencil. A drawing on paper that employs linear perspective arguably creates a virtual space.

I wanted the 3D virtual drawing experience to be an extension of my drawing and printmaking aesthetics, styles and motifs. This precluded using colour and patently extravagant brushes. I settled on a line quality that seemed to imitate crayon. The Tiltbrush is a very coarse medium relative to traditional drawing materials and 2D digital drawing materials such as the Cintiq. Obviously this will improve in the future.

The onslaught of digital technologies in recent decades has made the mass production of images ever more frenzied, and this effects the value of images and how we experience and perceive images. This necessarily effects the perceived value of artists as well. The experience and appreciation of even relatively modern visual mediums such as theatrical film are being rapidly degraded. As film maker David Lynch has wryly observed about the degrading effect of not seeing film in a theater '...it's such a sadness that you think you've seen a film on your fucking telephone!' . We could apply the same sentiment to drawing, painting and other visual art forms. Will VR provide a deeper and more considered visual experience as a result of the spectator being able to immerse themselves in drawing or painting? Or will its capacity for endless digital replication relegate VR to the ubiquity of other profligate digital media? At the moment VR enjoys a modicum of novelty and therefore perceived value. How long before VR art joins today's interminably replicating epidemic of mass produced images? How can the working artist make a commodity of VR? The very existence of trained working artists requires what they produce images, objects and artifacts of value. Mass production, and especially digital mass production are so excessive they undermine this aspiration. Whatever existential impacts technology and constant change will have on the artist will be part of what it has in store for the future of all meaningful work, for human dignity, culture, civilization and even our survival as a species.

At the time I did not what to appear ungrateful for the three hundred dollars, the opportunity to use the VR technology and exhibit some of my prints, but I hope you can sense a tactful questioning of, and less than enthusiastic endorsement of the technology. For the most part none of the other artists or children or their teachers seemed to fundamentally question the technology and it's effects on artists specifically, and humans in general. There was a giddy enthusiasm from the participants including the gallery. In retrospect, after the fact, the whole thing seemed surreal, or at best unreal. Why throngs of children in a public art gallery? How can an adult visual discourse take place in their presence? My David Lynch quote was censored which reduced it's fucking effect. (The issue of children in art galleries will be the subject of another post). None of the children seemed to have been made aware of how robotics have in the last few decades undermined the value of human workers and caused job losses and social upheaval. Would they like their mummy and daddy replaced by robots? Like all the spectators at the opening, the children were deprived of an awareness of the negative consequences of technology that might have been provided by the artists, the gallery technocrats, parents or teachers. The show was unbalanced if not completely unhinged. A public art gallery had essentially become an advertising platform for a large tech corporation (Google) and high tech in general. I presumed the dream of the children and especially the parents was that they might one day become the highly valued well paid employees of these corporations. Certainly not to become visual artists. I was confused and even disgusted for days after the event and the experience. I found it hard to believe that a contemporary art institution and artists working in it's confines should have been reduced to such conformism and malleability to the promises of technology. It appeared that, in my own community and perhaps in general, we could no longer look to the arts or artists for sober second thought and reflection.

If you want to view David Lynch's i-phone 'commercial' click HERE.

If you'd like to see what other participating artists said about the VR experience you can still find the CVAG's page on the project HERE.

For comparison, above, a screen grab of my Tiltbrush VR drawing with an actual drypoint print I was working on at the time. I think it's fairly obvious that both images suggest the possibility of the unleashing of some kind of miasma, plague or technology which I felt was appropriate at the time.

On the Art of Abu Zubaydah

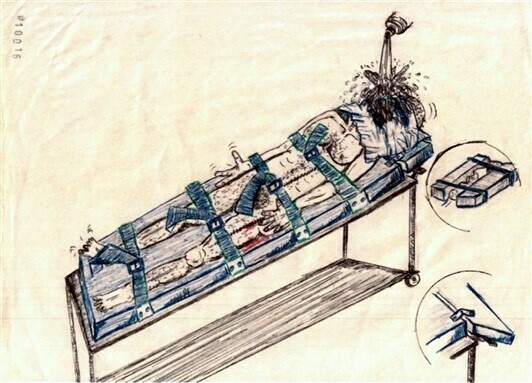

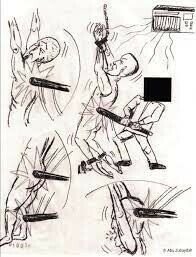

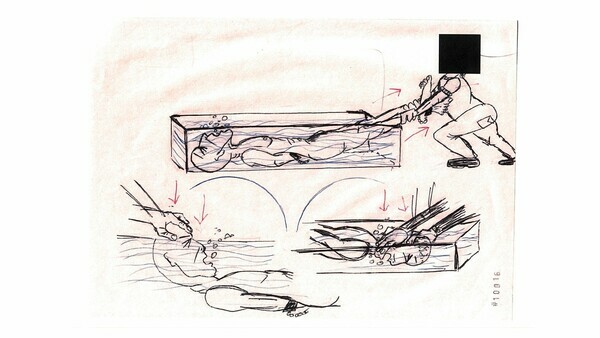

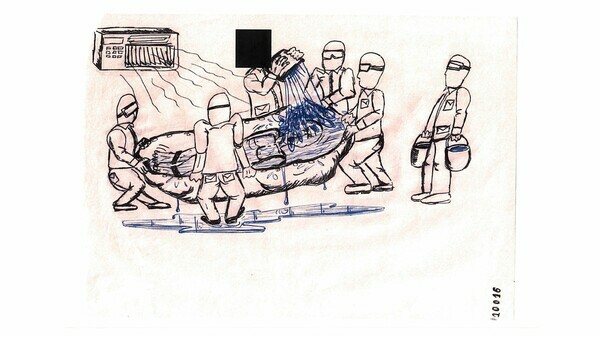

Above, drawings by Abu Zubaydah, depicting his own torture.

Abu Zubaydah has been in and out of the news for many years. I was vaguely familiar with his astonishing story through watching Adam Curtis's documentary Can't Get You Out Of My Head. A few of Zubaydah's naive drawings documenting abuse at the hands of US interrogators at Guantanamo Bay have been previously released and appeared in news items. Recently 40 drawings including new works were published as part of a report called American Torturers by The Center for Policy and Research; for a news item which also includes the full report click here.

This longish post will consist of a series of observations and comparisons of torture and figurative art, relating to the drawings of Zubaydah and the excellence or lack of excellence in drawing. As a visual artist I cherish excellence in drawing skills more than any other visual facility. I can't think of anything more significant to the visual arts than the coherent and skilled describing of form. Drawing is looking...and more...describing...and there is no keener way to observe and visually respond to the world. Observational drawing is connecting the eye, the mind and the hand through the body and there cannot be many more lucid ways to exist as an embodied entity in the world. Drawing, vast amounts of practicing it, (I mean tens of thousands of hours not simply taking a drawing course for a credit or prerequisite), allow an aspiring visual artist to make some sense of substance and matter and accumulate an inventory of mental templates of abstract biomorphic and geometric forms that can be recognized in the the chaos of the observed world or used for spontaneous visualizations. Delineating with rare skill requires hard work, enormous quantities of time and patience, and an enormous amount of enthusiasm to acquire. To have put in the time and effort to learn how to draw with excellence is, for me, an indicator of how seriously a visual artist takes their calling, their vocation. I rarely have time for artists who are too lazy or arrogant to put in the effort to learn and retain the ability to draw well. Similarly I would probably not be interested in reading a book by an author who never bothered to learn how to read, or watch a movie by a filmmaker who had never learned how to use a camera. Abu Zubaydah's drawing skills are dismal and childlike. But I'm going to make a case that Zubaydah's clumsy childish drawings might transcend a threshold between naive illustration and diagrams into 'art' due to his profound experiences.

Torture is appalling. I can't imagine it is in any way a practical method to wrangle information out of anyone. I'm certain I would tell my torturer anything they wanted to hear. The most practical way to obtain useful and accurate information from me, if I even had any, would surely be to park me in a comfortable bar with The Swingle Singers playing, buy me copious amounts of alcohol, strike up a conversation, feign interest in what I have to say, and ask me questions. If this would work for most other people this leaves me with the appalling conclusion that torturers represent an element of society who enjoy cruelty, and are ready and waiting in the wings to spring into action when organizations, government, death squads military or criminal, mistakenly believe their cruel services would be of value. Torture might be as human a quality, for at least part of the population, as compassion.

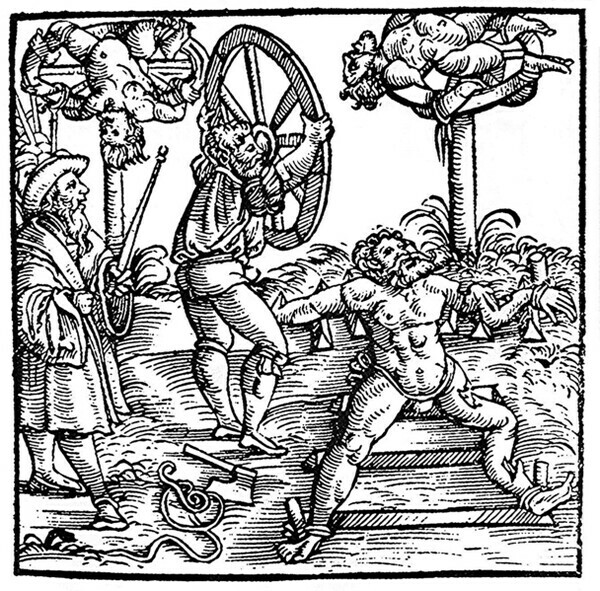

Perhaps torture's inhumane 'humanity' explains it's presence as a recurring theme both in history and the art historical record. Those records seem relatively flush with depictions of the inflicting of pain and brutal dispatching of people for various reasons; punishment; interrogation; inquisition and even public entertainment, as in events at the Roman Colosseum or medieval public executions. It has to be accepted that a portion of human society must enjoy inflicting pain and suffering on others and a segment of society must derive a sordid pleasure from watching such carnage.

Medieval torture and executions with The Breaking Wheel.

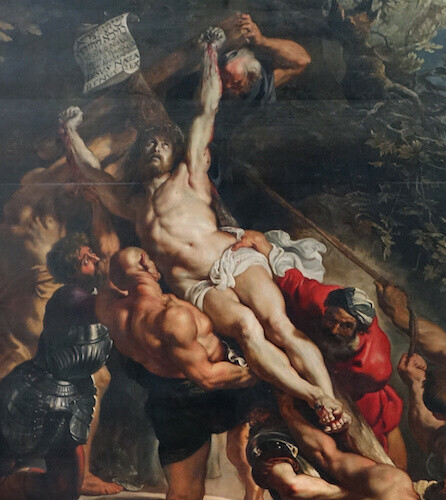

I grew up Catholic so was from an unnervingly young age exposed to a visual record of torment celebrated by The Church from gory crucifixions in the building itself but also in the glossy catechisms I used to browse during the tedium of mass. I recognize to this day the mortal human flesh of the Saviour, saints and martyrs, being inhumanely dispatched in paintings by Rubens and Caravaggio.

A crucifixion by Rubens memorable for me to this day.

As unwholesome as this exposure was, I'm not regretful; my exposure has assisted with appreciation and understanding of a great deal of art. So much of the Western art historical record derives from Christian sacred art and ritual, and before the advent Christianity, from equally bloody sacrificial and slaughterous rites. There is a long lineage of sacrificial myth. Sacrifice, of humans and then animals, has been a creepy fascination for humans over the ages. Julian (The Apostate), the last pagan Roman Emperor, was horrified at upstart Christians hurling themselves at martyrdom like suicidal brain infested zombies, yet on a daily basis he slaughtered quantities of animals for the purpose of divination. There must surely be a link between cruelty to, and the slaughter of, both animals and humans, as we are made of the same stuff.

In a neighbor's garage I once bore witness to the butchering of a bear carcass and painted it.

Catholic thinkers like Rene Girard appear to believe human culture was founded on murder and the mechanism of scapegoating and I would not find this unsurprising. At the very least my Catholic exposure sensitized me to the mortality of the flesh and the body's frailty to disease, damage and dismemberment. I consider a lot of art in the figurative tradition, both sacred and secular, to be about embodiment...and disembodiment. I've spent vast amounts of time as an artist observational drawing from the disrobed human form; life drawing. It often occurs to me that many of the souls whose mortal flesh and bodies I have drawn and studied so intensely are now dead. There's a paradox in humans revering the nude and torturers stripping their victims naked. The clue might be in 'naked' vs. 'nude'. I can't draw from life without realizing that before me is a mortal human like myself, born to die. My mirror neurons are presumably stimulated. It is always my hope that this somehow comes through in my drawings in some small way. But when we strip someone naked something completely different seems to happen; the naked are vulnerable to abuse, reduced to animals, less than human; as depicted perhaps in medieval and Renaissance scenes of hell and judgement in churches.

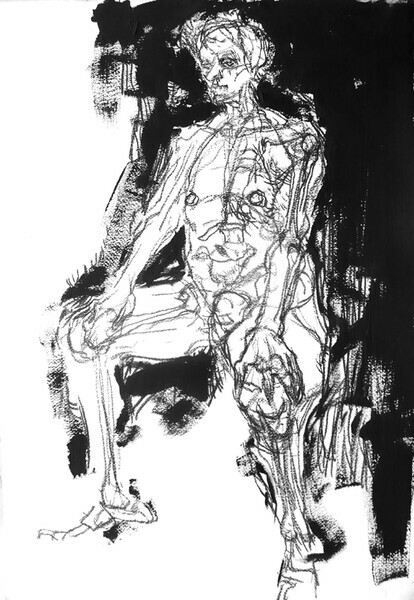

A figure drawing of my own.

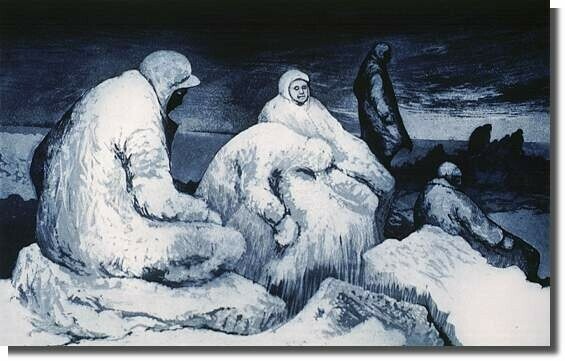

When instructing students figure drawing I often tried to bring attention to the notion of creating groups of figures. We have an ingrained evolutionary fixation, I suspect, to be deeply interested in interacting groups of people. We're social primates who form interacting troupes and are deeply interested in what clusters of our kind are doing. All the crucifixions and flagellations and portrayals of Biblical events are essentially groups of interacting humans. I recall the early prints of artist David Blackwood, who for a couple of decades worked on 'The Lost Party' series of etchings based on a weather related sealing disaster off the Newfoundland coast in 1914. An erudite person I knew claimed that if Blackwood found the lost party he'd be out of a job. The exceptional series of prints was ostensibly about 'The Lost Party', and that Canadian-content historical attribution surely contributed to Blackwood's success. But, content aside, at a deeper abstract level, it seems to be intriguing arrangements of human figures in a sublime and desolate location that may be most transfixing. Not the content. Not to take away from the poignancy of Abu Zubaydah's bearing witness, this might also be true of what he is also presenting, beyond content, beyond message, and beyond documentation; groups of hominids interacting in fixating, unusual, indeed profoundly disturbing ways. Zubaydah's drawings have this in common with the greatest examples of figurative art.

A print from The Lost Party

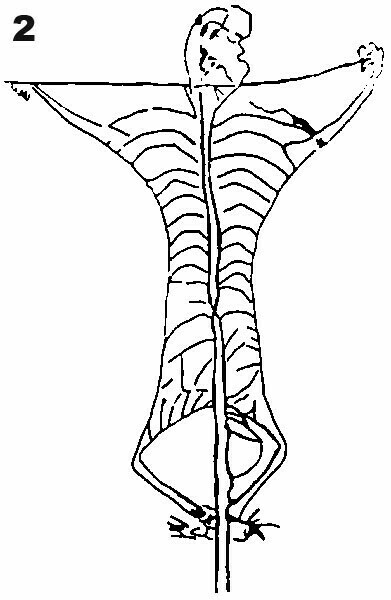

Zubaydah's drawings are naive to say the least. At best they are junior high school level. Jean Piaget documented predictable phases of children's drawing from scribbling, to circles, to cephalopodic figures with crude appendages, to full frontal figures, and finally, attempts to express action, dimension, perspective and proportion. Zubaydah's drawings seem to be on a par with the final predictable phase of children's drawing, generally that of a child about 10. Piaget claimed estimates of age and IQ could be made fairly reliably from perceived complexity. Every child draws and progresses in skills until, at an almost predictable age, around ten, most stop drawing. Those few who continue to draw used to be the sort that went on to attempt to be artists. After children become youths the predictable succession of development as described by Piaget for young children ends and it becomes difficult to estimate age or IQ beyond that threshold; factors such as training, social distractions, hormones, sports, schooling, opportunity and aptitude come into play. Zubaydah's drawing facility seems on the cusp of the transition from childish drawing to that of adolescent youth, the final predictable phase of childhood visual development. Zubaydah might have an awareness of comic book presentation, and it's not inconceivable that he was aware of the visual arts. He might, for example, have seen of the profound, timely but disturbing figurative paintings of Leon Golub. Regardless, there is a perceived authenticity to Zubaydah's drawing which is not wholly derivative.

Leon Golub's envisioning of an interrogation

Authenticity is a huge concern for me; I've always tried to be honest with myself and with my art and have no doubt abjectly failed. There are degrees of authenticity which I suspect the best any artist can do is aspire to. Authenticity is not to be confused with novelty. There are wheels within wheels though; I consider Andy Warhol incredibly unauthentic, something he worked hard to achieve, which sort of makes him incredibly authentic in his honest and forthright un-authenticity. Does that make sense?

Back to drawing, there is a risk for an artist that, as skills accumulate, authenticity diminishes. This doesn't have to happen, of course. An artist doesn't have to merely create clever drawings if they can delineate with rare skill. But it's easy to fall into the flourishes of clever slickness. In observational drawing it is easy to stop looking. I often confessed envy to and for my beginner drawing students as I instructed them in observational drawing, measuring angles and proportions, creating pictorial depth and perspective. I saw them struggling to focus and observe intensely, draw adequately and the results were drawings that, if slightly naive and riddled with corrective errors, are nevertheless stunningly authentic and moving to look at. The corrections, the pentimento, document the struggle to will form and structure to emerge from line work on a page, and this seems to create an recognizable authentic aesthetic. Their searching line is to be savored.

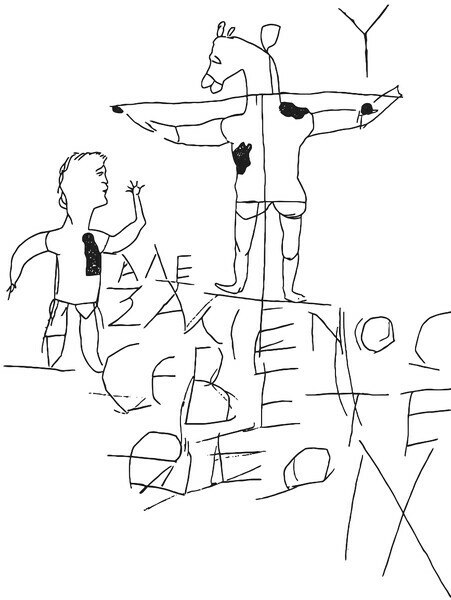

Here, below, even more primitive than an observational art student drawing, is a rubbing of a second century naive unskilled inscribed graffito on stone depicting a crucifixion for comparison with the Rubens above. The carnal, almost animal nature of the crude drawing is compelling to my eye.

For further comparison, below is a rubbing of a graffito of a crucifixion from around the same time which may or may not be one of the very earliest depictions of Christ's crucifixion. The inscription says 'Alexamenos worships his God' so the object of the drawing is something of a 'cartoon' mocking Christians and Christianity. That might be Alexamenos with the asses head on the cross 'worshiping his God' through crucifixion and being mocked by a passerby, or it might be Christ himself being crucified with Alexamenos as the observer 'worshiping' his God. Either way the asses head is the biggest clue to the intent of the drawing.

Compelling drawing is usually achieved (for me) by an enormous amount of looking and and executing, and at least ten thousand hours of practice (according to lore). But sometimes I suspect, circumstances, experience, emotional response (and sometimes coincidence) allow for an aggregation of qualities that make someone unskilled (child, adult prisoner, adult mental patient...) take an excruciatingly painful shortcut to exceptional visual art. Here's an anecdote to try and demonstrate this. I was once teaching a summer outdoor sketching and painting class through the very college I had attended. There were serious students, looking to learn and receive credits in the hope of getting occupations in art, but also dabblers. One such older dabble had very little ability, drawing skills of about a ten year old. My task at best would be to provide her with an interesting three weeks of self actualizing entertainment and perhaps coax her to improve skills without devastating her confidence. She was sitting drawing on a stump, drawing another student sitting on a stump with Lake Ontario and a chaotic arrangement of sailboats in behind. The drawing was dreadful but the figure, the arrangement and the chaotic array of sails struck me as haunting. The hairs on the back of my head went up. 'Good God' I exclaimed, 'It looks like there's been some kind of terrible accident!'. Out of the corner of my eye the woman slumped over and and burst into tears. It transpired that her son had committed suicide two weeks before the start of class and she'd almost not shown up. 'My God; that is all in the drawing' I said. I would consider her drawing one of the most profound images/works of art I've encountered first hand; up there with Pontormo's Deposition. It gives me the shivers to relate this story to this day. For me it's the emotional and painful human circumstance of the drawing's genesis that made it compelling and pushed it across a boundary between a naive scribble and into art. Similarly, I suggest, with Zubaydah's drawing. I don't think that unskilled drawing is usually capable of becoming art, except in astonishing instances like these.

More on authenticity. You know when illustrators (or artists) try and make something very contrived look loose, compulsive and sketchy? As if it were just dashed off? How fake it looks? The illustrators sketchy look is 'affected'. I could recognize this falsity even as a child. Those sketchy scribbles surrounding an illustrated form didn't look authentic; they didn't look like the kind of genuine pentimento you see around a Renaissance drawing study, where the artist is feeling out the form stroke by stroke and finally recognizing a true contour to fortify. You can see the work, the effort in the authentic drawing. The skilled illustrator or artist contrives a mere flourish. I admired my drawing students struggling to deploy drawing methods and techniques; their errors, alterations and efforts were genuinely observable in their drawing. They weren't faking it. Zubaydah's drawing skills seem inadequate in the face of the horrors inflicted on him but through sheer will and effort he manages to cobble together a rudimentary but compelling documentary vision of his abuse.

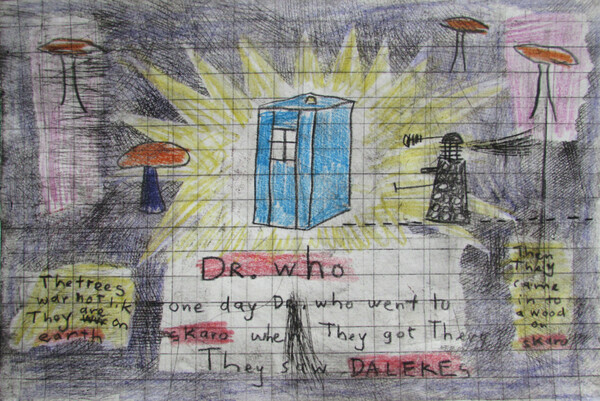

I have on a number of occasions tried to channel my former selves into my art, including my childhood self, and this has included actually using old drawings, teachers admonitions and attempting childish drawing as an adult. I didn't have anything particularly dramatic to communicate from my childhood, except the effect of television, which entranced me at the time, and in creating a series of child-like prints/drawings I perhaps hoped the results, if banal, might at least be an authentic representation of something or other...perhaps the dramatic effect on childhood of television. Like so many quests for an authentic vision, if my outcome lacked authenticity I at least hope the effort didn't. I also hope this particular anecdote provides some background to my fascination with the notion of naive unskilled drawing and complex skilled drawing. It is as though if you are extremely interested in good drawing you must also have a reciprocal interest in bad drawing. You can't comprehend up without down, nor sweet without sour.

A chine colle drypoint print and drawing I made from my childhood Dr. Who drawings.

Let's consider one another comparison to Zubaydah beyond children's drawing; the art of the insane. John M. MacGregor was an invited art history instructor/lecturer at the College I attended, and he taught a course on the art of the insane whilst writing his book on the subject, which appears to be the first, if not one of the first comprehensive tomes on the subject. Our college was structured on an arts and crafts model; working artists and artisans taught prospective artists and artisans. There were drawing and painting studios, printmaking studios, illustration departments, a textiles department, a modest film and animation department, an 'experimental arts' department, and a foundry. It was very hands on. Academic or Liberal Arts courses were provided and they seemed intended to provide background and general knowledge for working artists rather than create serious academics. There were the standard 'Survey's of Western Art', which often amounted to slide shows but there were also some more unusual courses, for example, on early Christian and Medieval art, and, MacGregor's course on the art of the insane. I didn't actually take MacGregors course, regrettably; you just couldn't cover everything and working with your hands to acquire skill is extremely time consuming, but a number of years after college I was teaching there and had chats with MacGregor at the photocopier. I got hold of his book which is relevant for anyone who is an artist of 20th century vintage or interested in the era. 'The Discovery of the Art of the Insane' shows just that, how the discovery of the work of mad persons had a profound effect on the work of 20th century artists. MacGregor points out, if I recall correctly, a considerable amount of the art world and artist's interest was Romantic in nature and plagiarist. MacGregor parses out notions surrounding the perceived feverish raw mad unskilled talent of individuals in mental institutions and provides a clearer vision of how and why compelling works of 'art' were created by the insane. For example, consider how difficult it is in this day and age in Canada to be a productive artist. Madmen and madwomen, confined to institutions where they were fed, clothed, housed, with time on their hands were sometimes encouraged to draw and paint for therapeutic reasons and furthermore received positive feedback for doing so by staff who were genuinely interested in documenting and understanding their afflictions. They were given a space to create which is much more difficult to find in the outside world. MacGregor also shows that many mad artists were actually artists on the outside prior to incarceration, and those who weren't, and had no training whatsoever, were given the time and space to develop and unleash their naively executed fixations. Child-like skill could, as with the incarcerated Zubaydah, be focused in the production of detailed imagery with a disturbing and compelling point of view. The art of the insane, indeed psychology and psychotherapy, nevertheless deeply effected 20th century artists from Surrealists to Expressionists to Art Brut, Outsider Art, and even Stuckism. MacGregor provides examples of what is close to copying the work of mental patients by Man Ray and Jean Dubuffet, and by looking at art by artists I often notice similarities myself.

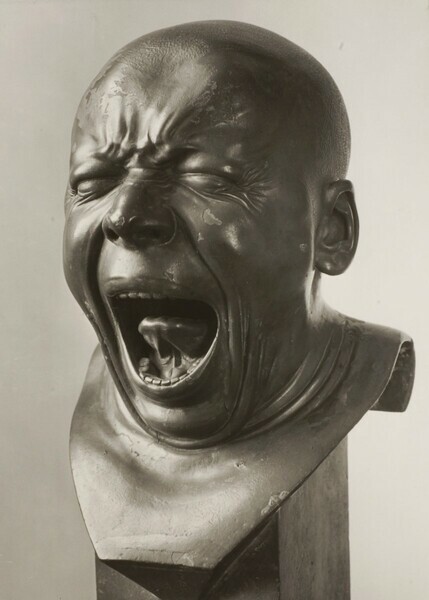

A sculpture by accomplished 18th century sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt who was afflicted with paranoia and hallucinations.

Canadian sculptor Mark Prent.

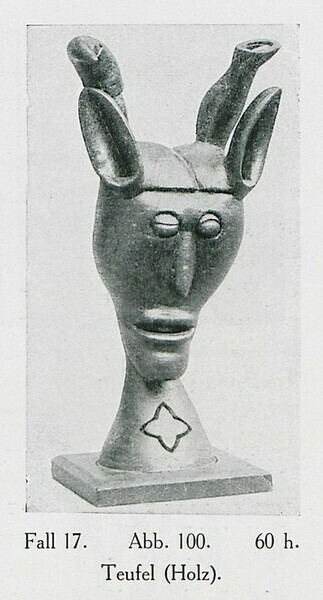

A sculpture by mental patient Karl Brendel in the collection of the Prinzhorn Collection, 'Devil', and a sculpture by Max Ernst 'The Imbecile'.

I believe Abu Zubaydah's appalling experiences may mainline his art into a place of special consideration. As an artist I like to pay close attention to an image's visceral artistic qualities. There are historical and contextual considerations to Zubaydah's drawing which are beyond my expertise, but as an artist I'm drawn to his work for aesthetic reasons and would without doubt make a point of seeing an exhibition of his drawings in a not dissimilar way that I would a skilled and well known artist of note. Zubaydah's drawings will exist in the historical and, I hope, the art historical record along with other great images of human manufacture from the past and future.

As a final note, more sinned against than sinner, one hopes very much Zubaydah is released and is provided compensation for his torment and finds a modicum of peace in what time remains for him. As well, one hopes that the criminality of 'extraordinary rendition' and accompanying torture and abuse will one day be recognized more widely and in court.

Alien

At the beginning of 2023 I posted an 'exhibition' on my website of drypoint prints that had been drawn from Midjourney text-to-image AI prompts and then tinted with tea and watercolour. Using a short sentence to describe how I made my prints I asked ChatGP3 to compose an artists statement for me. It appears to me that the AI made surprising inferences about aesthetic choices. I find the results astonishing and terrifying and here they are in italics:

"As an artist, I am intrigued by the intersection of technology and traditional art forms. In my work, I use text-to-image AI to generate unique imagery, which I then translate into drawings and drypoint intaglio prints on 11x15 inch paper. I use a technique of tinting the prints with watercolour, coffee, and tea to add a sense of depth and texture to the final pieces.

I am particularly interested in the ways in which text-to-image AI can be used to create unexpected and surreal imagery. The algorithm's ability to generate images from written descriptions allows me to explore the relationship between language and visual representation in new and exciting ways.

The use of traditional techniques such as drypoint intaglio printing and hand tinting with watercolour, coffee and tea, adds a sense of warmth and humanity to the pieces, and creates a contrast with the cold and calculated nature of the AI-generated imagery. By blending technology and traditional art forms, I aim to create thought-provoking and visually striking works that challenge the viewer's perception of reality."

To be completely honest, this isn't necessarily what I would write, or say, about my series of prints. In fact, if I wanted to 'say' something I would just say it, and not make an image. I believe it is most sensible to say nothing at all about an image and let that image communicate accordingly...I hold this belief despite the unfortunate fact that my verbal mind is not easy to shut up and will incessantly try to explain an image. When I do suggest something about an image in writing the text assumes far too much meaning and importance relative to the image because the verbal mind has such control over what might be assumed as consciousness. A written statement compresses and simplifies the wider spectrum of interpretation for the viewer. It closes doors in the mind of the viewer. What the AI has done is write something I would write if I wanted to do what most artists want to do when writing about their; write something clever and thoughtful with a few artsy buzzwords to please curators and members of the public who want to have the meaning of what they are viewing distilled into a few paragraphs in what I nevertheless believe is a mistaken assumption of understanding. It has done this incredibly well.

It takes a lot of thought and time for a human artist to come up with a clever and comprehensible artist statement, and most visual artists don't seem particularly good at writing...unless they in fact are good at writing and are deliberately trying to write in an opaque and difficult to understand manner in order to suggest that it is in fact their work is difficult to understand. Which is sort of clever too. So there might poorly written art statements, clever and comprehensible art statements by artists, and clever and incomprehensible art statements by artists. It's often difficult to parse out which is which. The chatbot's statement seems to me of the kind that is clever and comprehensible, and astonishing as such. I presume, if prompted accordingly, it could also produce a clever and incomprehensible statement.

I really can't see why most artists who struggle with writing a clever artist statement (of the comprehensible or incomprehensible kind) would not simply task Chatgpt with the job. And I also can't see why any artist would waste time and effort crafting several paragraphs when, within a few minutes, Chatgpt can generate a series of examples which can be selected from. We might be entering an era when machines speak for artists, and potentially, all of us.

The Last Invention

'Machine intelligence is the last invention that humanity will ever need to make'. Nick Bostrom, Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford

The following is a short 'essay' of sorts that I wrote to accompany an 'exhibtion' I posted on this website in January 2023.

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image

Here are my own (not machine generated) human observations and opinions of the experience of working with text-to-image AI, and also some thoughts about the technology from the point of view of an occupational fine and applied artist. I'll be curious to re-read these impressions a year or two from now to see if my current AI anxieties still exist. There are some links in bold font.

Thou Shalt not steal

There seem to be two opposite views of the AI/art issue; one is that high anxiety is hysteria and moral panic and that this technology is just another technology (often compared to photography). The other view is that the technology is not like previous technologies, and that we are treating it with a 'normalcy bias' and human prospects will continue as usual. There are presumably many views in between. But given the abilities of text-to-image AI in these very early days, and generally confining speculation of AI's effects on the role of occupational artist in our society, my situational awareness in regard to AI is on the side of high anxiety.

I expect text-to-image AI to be catastrophic for visual artists. AI is not a tool for artists, it's a replacement of them. Artists are a means of production and AI is a vastly more powerful means. I would be enormously happy to be mistaken about this. Currently AI is owned by corporate entities often acting under the guise of being 'research labs' and use 'data laundering' through researchers to steal from human artists with low risk of copyright infringement. Compare AI to Amazon Mechanical Turk ('artificial artificial intelligence), in which human workers are exploited by being poorly paid for micro-tasks that are aggregated by machine. Anyone who is exploitable has value and at least some small degree of recourse to react against their exploiters, particularly when organized. The current text-to-image AI is structured to steal art from human creators for no compensation by scraping the internet of their work to make images. This makes artists of even less value than others who are exploitable. AI thievery, by removing value from human artists leaves them with nothing of value to bargain with for compensation. Contrary to cunning public relations and advertising campaigns I fear there may be no safe 'collaboration' between human artists and machine imagery because the power relationship between them is so asymmetrically in favor of the AI and the corporations behind it.

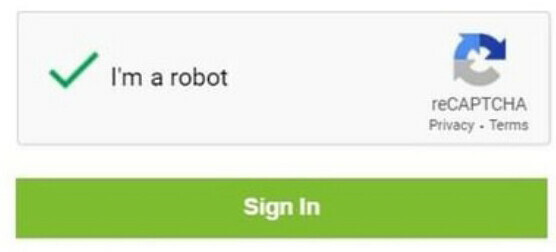

The machine in the ghost

I don't believe there is such thing as a human 'AI artist'. Humans are mere operators of machine intelligence. Consider that humans who have no awareness of how to describe form or make visual art can now with a few words prompt an even more unaware machine intelligence to generate astonishing results that can be mistaken for the work of trained human artists. We aren't talking about a sentient machine intelligence. This is a chilling, empty, oblivious, zombie intelligence that even in these early days mimics the results of human creativity such that experts cannot reliably discern what is AI and what is human. I might delude myself into believing that I can reliably perceive which of two images is human and which is AI. I might convince myself this would be the result of my practical art expertise, experimentation with, and observation of, AI and it's foibles. But I would usually have to end up guessing and would probably do no better than anyone else. By contrast, AI itself will do a much better job of recognizing what is AI and what is human, that is, there might be AI apps that can more reliably discern what is probably an AI creation; text, art, film or photo. Think of apps like Pl@antNet which identifies herbs and other flora. You simply photograph something and, depending on the quality of your quick snap it will give you astonishingly good percentage probabilities of the species you are looking at. Several similar species and their probability of matching will be further supplied in mere seconds. Consider also facial recognition. Beyond the issue of 'what is art' AI raises, entity fraud, AI's ability to fake human creativity, has alarming implications for human society and human connection, with the only way of discerning authenticity existing being a similar machine intelligence. For me, anachronistically perhaps, it has always been the humanity of art and literature that has has provided empathy and wonder. Art objects that we believe to be fabricated by other humans with fears and desires not unlike our own don't just communicate with human observers, but, through emotive recognition observers feel able to respond back. Believe no more, and even if we respond to AI art all it will do is collect our data and mechanically use it to make more of the stuff we want. With AI there is no entity to connect with, although we might be fraudulently led to believe there is. At least until if and when a self aware artificial general intelligence comes along (this is also anxiety provoking) we will be interacting with philosophical zombies that 'pass' our best Turing Tests. We will not know what is authentically human and what is a machine hallucination; their hallucinations will be ours. Hallucination and losing touch with reality has previously been in the domain of mental illness. We already exist in a digital world with vast quantities of false and untrustworthy images and information that feed paranoiac and delusional highly infectious conspiracy theories that seem analogous with mass hysteria. It is probably going to get worse.

It's a strange world after all

As a visual artist I aspire to observe and represent the world, and in doing so often shift to an uncanny, surreal, non-standard viewpoint in order to emphasize the strangeness of a visual world most non artists take for granted. Being from the 20th century I have believed this aspiration is shared by other artists and is one of the qualities of interesting and, if you will, 'good' art. I discovered that by limiting prompts in AI a similar uncanny quality can more readily be induced. AI art imperfections in these early days make results more surreal, abstracted, interesting and art-like.

'Experts' (not surprisingly in this day and age these are considered to be critics, art historians and gallerists rather than actual working artists) look for 'flaws' in the AI art, as do most people making comparisons. This is odd considering the similar extensive 'flaws' in human art. AI is currently notorious for frequent anatomical distortions but consider and compare the distorted figurative art of great artists like Pontormo or Ingres or more modern artists that further stylize and distort the human form in uncanny surreal ways.

In comparison to AI art, as a trained working artist I (nevertheless subjectively) perceive an enormous amount of human art to be not very good. Whereas it seems to me from using AI an enormous amount of AI art is quite good to very good and is furthermore produced almost instantly. Because even better results after results can quickly be generated, AI exponentially outpaces the efforts of the human artists it steals from. As a working artist I have worked long and hard for days, weeks or months and failed to come up with anything that I considered 'good' or even acceptable to my (nevertheless subjective) self. For human artists, the exceptional is truly the exception.

Anatomically freakish Ingres drawing.

Curationism.

AI produces images/art rapidly and in enormous quantities. It is cheap. It will meet deadlines. It won't be petulant. It won't call in sick. It won't become constipated with creative blocks. It won't drink or take drugs. It won't succumb to despair. And it won't condescend to whoever requires its 'skills' or services. It will fulfill a much beloved contemporary art neo-Duchampian 'curatorial' dream for operators who will be gratified with a sense of delusional authorship for what the AI has generated.

Why Bother?

I suspect artists 'good' or 'bad', are increasingly thought of as 'content providers', an appalling term which demystifies and undermines traditional notions of art as something 'made special'. As content providers visual artists will never ever be able to compete with the content provider AI. The day may be fast approaching when almost all cultural content is produced by machines that, as a result of having access to personal data, will be able to accurately predict what you desire when you want to look at visual art, watch a movie, read a novel, or listen to music. It will then provide content so tailored to your sensibilities that you will consider it your own, identifying with it as with a brand. This will provide incredibly entertaining content. But that content might also be the painting you vaguely imagined you might create. Or the novel you had in mind. Or the movie or music you imagined you'd compose. AI might not just steal from past artists, but also future ones. AI might steal from your imagination well before you can create a work of art. (Ever wonder how Amazon manages to so quickly get a product to to the region you live in?) If you do in fact undertake a creative process, it will take so long AI can in the meantime make quantities of similar iterations to your content, most of which will be as good and much of which will be better. As an artist I confess that using AI to conjure imagery leaves me with a gnawing question for the future. 'Why bother?'.

Unstable Diffuser

Almost as soon as Midjourney text-to-image AI became publicly available I subscribed and tried using it as a tool, something I believe it was not designed to be (AI being a means of production and replacement for artists). I used AI to generate compelling (for me) 'unnatural-natural' forms and 'folk' forms from which to draw. These drypoint prints are a product of rediffusion; diffusion from nature by an artist other than me in their renderings, diffusion of those renderings to the internet, diffusion from those internet images being 'scraped' and transmogrified by machine intelligence, and further diffusion by my elaboration, re-drawing and printing. If diffusion describes broadcasting (from the French) information rediffusion describes re-broadcasting. When I was a child there was actually a broadcasting company called 'Rediffusion' which rebroadcast radio and television programs on it's networks. I thought the name might make a good title for this 'exhibition'.

It's worth considering the six months of regular sustained effort it took me to create these drawings and prints from AI reference to the minutes that would be required to generate a similar quantity of AI jpgs that might be similarly compelling and apparently human.

Logo for Associated Rediffusion.

File under futile

A way of looking at my simple and straightforward approach to AI is as a morphing search engine providing images not 'of' but 'in the manner of' the sort of thing I've consistently been interested in over my visual life. When I walk on a beach or through the natural world and pick up and collect forms that interest me or that I might like to draw, I am a bipedal search engine. Like many artists and illustrators I collected art books and magazines for reference and ripped pages out to put in labelled files in cabinets as searchable accumulated visual reference. More recently I created files in my computer of a vast number of things visual that interested me during image searches. For this exhibition I searched for and created jpg reference files of AI generated material to work from.

All watched over by machines of loving grace

I've long been interested in AI and it's potential, like so much technology, to either create a utopia or a dystopia that would deprive humans of paid work, meaning and dignity, or much, much worse. I was astonished at AI's early arrival in my own apparently innocuous occupation, the visual arts. I find it worth bearing in mind some of the deeper general motives behind the development of AI, for example the quest for autonomous weapons. The worlds first autonomous weapons already exist and this prospect is so alarming that even some scientists who work with AI have issued warnings about how the technology might unfold. It is easy to envision AI research as an arms race between world powers. But minor powers and groups can be part of this new, non-nuclear, arms race because the weapon of AI does not require an extensive military industrial complex and therefore AI weapons will be easier to produce and proliferate. I'm not adverse to the miracles of technology and science, but I'm from an era when scientists were regarded with a justifiable degree of suspicion for their role in creating weapons of mass destruction and technology with unintended consequences. If you consider the greatest existential risk currently assessed by experts in the field most of what threatens to wipe humanity out is technology and science. I'm often perplexed at the cult-like enthusiasm for scientists today, relative to how they were often viewed in the past.

Dr. Strangelove, from the Stanley Kubrick film.

Erewhon

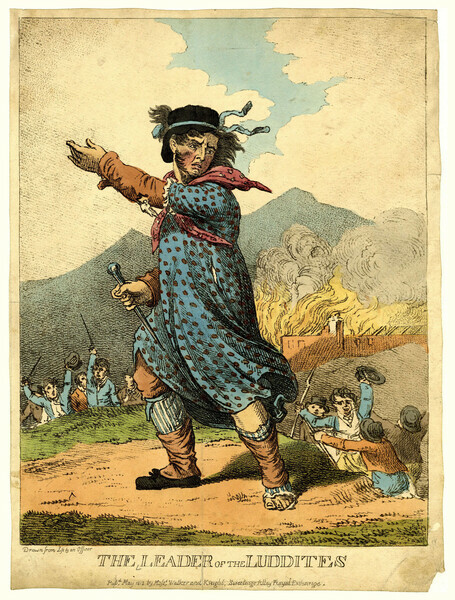

Luddite is a word that is now generally used in contempt. But I have a fonder attitude toward the Luddites of days past. Their lucid situational awareness provided a correct assessment of the threat of machines to their livelihoods and way of life and despite persecution they made attempts to leverage their weakening position through vandalism of machines (for which some were apparently executed. They failed in their quest and mechanization and operators replaced them. In the imaginary future Dune's Butlerian Jihad is a holy war in which humans rebel against thinking machines. They succeed. In William Gibsons Neuromancer the Turing Police stifle any untoward advances in potentially dangerous AI. Vandalism, Jihads and policing aside, one of the better hopes for containing 'AI art' might be litigation, considering the original sin of text-to-image AI is theft. At the time of writing these observations a class action lawsuit against some of the larger corporate AI players has been initiated.

Ned Ludd, alleged founder of the Luddites.

I have little interest in artist's statements, and never want to write something that explains in words what I might be doing with images. I never want an image to 'say something'. If I want to say something I just say it, or write it, which would undermine the purpose of making visual art. However, artists and curators statements are an (annoying!) part of the contemporary art experience and so at the top of the page I had the AI text generator Chat GP-3 generate a couple of paragraphs.

My observations about AI are mainly to do with images. It has been a premise for artists, and certainly for me, that their unique contributions to the visual arts, no matter how modest, are nevertheless special and unique regardless of how well recognized, because of their humanity. The plague of unique images to be released by AI undermines whatever remains of that belief in me, which is saying something after having lived my life in an age of mechanical reproduction which had already steadily eroded this notion.

But I'm also astonished at how coherently AI writes. Both AI image and text generation seem to me to reveal how algorithmic, cliched, predictable and derivative most human creativity might now seem, including my own. If delusional overconfidence has been a problem for humans and human artists, a malaise of lack of confidence might be in store for humanity and add to the societal problems that AI creates. I suspect AI will erode the generally acknowledged human belief that we are all unique and have something special to offer by our industry and labour.

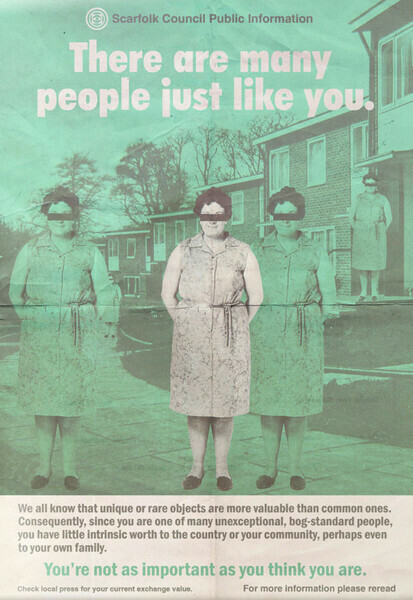

Scarfolk Council poster from an alternate historical nineteen seventies UK nails it.

For the love of humanity

A faint personal hope for the future of human art is that buyers and lovers of art will value what is human over what is machine made. However, history does not bode well in this respect. Consumers already prefer cheaper, profuse, high quality machine-made objects over more expensive, scarce, variable quality hand crafted human ones. In the visual arts the number of artists who offer machine produced reproductions is cause for dismay, as is the number of 'art appreciators' who purchase them rather than original art.

There is also the fact that humans can't actually tell the difference between AI art and human art, at least when reproduced on a screen which is how most art images are now viewed.

In my lifetime, when technology has previously replaced labour it seems to generally to have been the labour of the working classes. Anecdotally I've observed well paid factory and skilled trades work replaced by robots and CNC machinery. In retrospect there doesn't seem to have been an enormous concern by society in general for displaced blue collar workers who at the least seem to have been treated very shabbily after losing employment. Will the response to this new technology be different? AI seems as capable of replacing not just artists but also well paid white collar managerial arts technocrats such as curators, art educators and administrators. In society at large teachers, lawyers, programmers, doctors, journalists...knowledge workers...and many other professional occupations might face massive layoffs and redundancy. AI seems to have the potential to wreak havoc among higher value occupations and therefore might receive greater societal push back. For me there is hope in the trashing of intellectual and occupational elites by AI. Perhaps they'll throttle it's deployment to save their own skins if not the skins of ordinary folks.

The future is short

Just prior to writing these notes I cancelled my subscription to Midjourney. In what time remains to me I'm going to be more interested in what human beings do more than machines.

January 2023

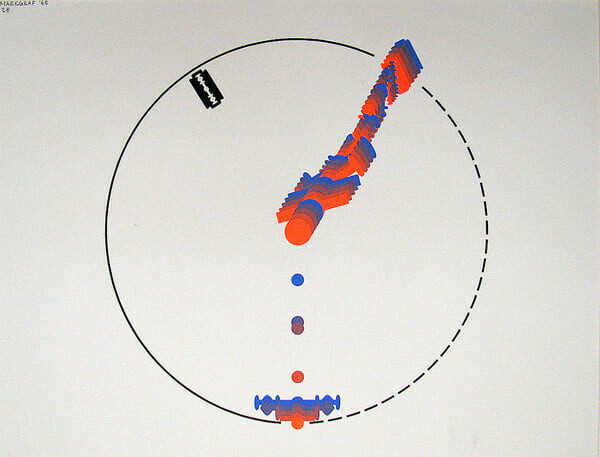

The Markgraf's

I discovered Peter and Traudle Markgraf around the time I left for art college and my family moved West; their own landscape silkscreens were to found in many galleries and I probably also saw them in magazines. A married couple, they studied art in Germany and arrived in Canada in the late 50's.

At that time the Sampson-Mathews Company had been producing oil based silkscreen prints on board as part of one of Canada's largest public art projects for several decades, and I remember the Sampson-Mathews prints displayed in my school, in the post office and other public buildings of my home town. The prints were part of a national culture building exercise, and promoted the work of some of Canada's most well known artists. For example, a print of Emily Carr's Sooke Church was outside of my grade six classroom. A. J. Casson was actually an art director at S-m's, and he enlisted many of his contemporaries including The Group Of Seven of which he was a member. The National Art Gallery also sold the prints, and they apparently found their way to embassies and military bases in post WW2 Europe. Although not what we might think of as numbered fine art prints, the prints were hand produced, considered to have value, although not enough to warrant special consideration and although not quite ephemera many were lost or thrown out. In recent years efforts have been made to market remaining stockpiles, and to buy and sell remaining prints, most particularly for a period by The Pegasis Gallery on Saltsprint Island. The Sampson-Mathews visual culture project really deserves it's own post, but for now more about Traudle and Peter.

Link here to Sampson-Mathews collection.

Back to the superb silkscreen artists Peter and Traudle Markgraf. Within a few years they essentially took over from where the Sampson/Mathews company left off, reproducing through silkscreen classics of Canadian painting for the National Gallery and a print distributor. At the time of writing the print company Artistia, out of Montreal still dealt in these 'early' screen prints which could still be purchased for 3-400 bucks. In the posted images below is the lush silkscreen reproduction of Varley's 'Vera', which apparently required over 80 colour passes with the squeegee to achieve it's effect. Looking at their work of this period, even reduced to a jpg on a screen, I can't help but admire the skill and technique required to work in the various styles of the various artists whose work they reproduced. In that same era, the 60's, a significant interest in silkscreen seems to have developed as a result of the popularity of post-modern, graphic, and often optical art; in the US this seems to have been spearheaded by the likes of Roy Algren, and in US online galleries you can find Markgraf prints along with Algren and others. If you like 'blends' you will love this stuff. I visited The Art Gallery Of Northumberland about 12 years ago and caught a superb exhibition of 'Markgraf prints'...during the 60's and early 70's it would appear the Markgrafs were involved with the production of of a folio of prints under the moniker 'Toronto 20' which included some of the big names in the Toronto area at the time; Harold Town and Joyce Weiland, Jack Bush, Robert Markle..., and Traudle's own work was included in this folio under her own name. Browsing online it appears the Markgraf's also produced silkscreen prints for the celebrated Anishinaabe painter Norval Morrisseau. The Markgrafs were obviously in great demand for their print skills.

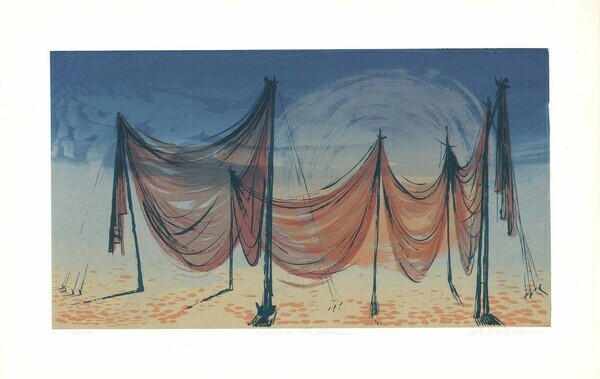

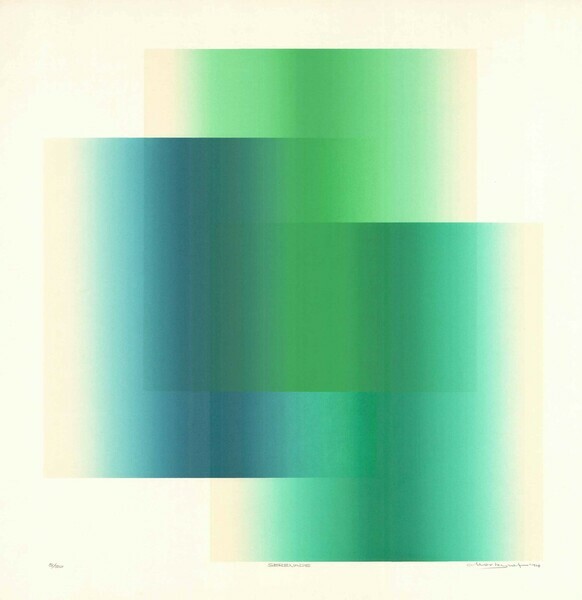

Sometime in the late '70's print 'work' for the Markgraf's evaporated due to the typical fickleness associated with the visual arts. They found themselves underemployed and so packed up and headed out on the road travelling west and finally settling on the Sunshine Coast where where they developed their final print line, consisting of their own creations, which utilized their facility with blends to create ethereal aerial perspective in prints of Canadian, and particularly West Coast, landscapes. This is the era I first encountered their work; up and down the island to this day you can pick up Markgraf prints of this vintage for a few tens of dollars in fund raising 'empty the attic' auctions (see last 2 prints) at public art galleries. They are often in their original ubiquitous 70's and 80's silver steel frames and potentially light damaged from years of enjoyment. After about 10 years on the coast Traudle apparently developed health issues related to printmaking and they packed it in and headed back to the Montreal area to retire. One final note; I have a hunch the Markgraf's started printing for BC artists Toni Onley and Stewart Marshal (the kayaking artist whose documentary surfaces over and over on the Knowledge Network, or used to). Or at least the Markgraf's set them up; there seems a distinct similarity in the use of blends, translucent ink and and high key grayed down colour arrangements. I think Marshal's prints of the coast are stunning; better than his watercolours, vast, stunning and crystalline.

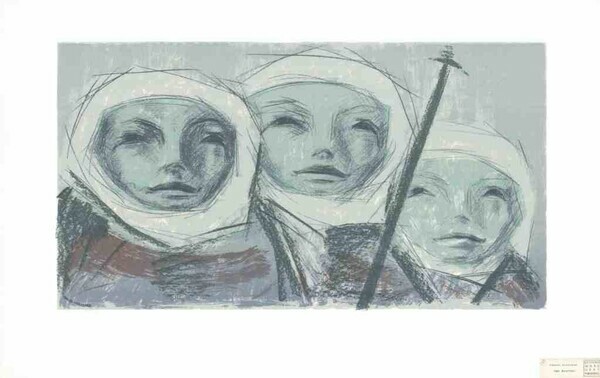

Below are some Markgraf prints showing the extraordinary versatility of their art and methods. Someone, somewhere, some time needs to make a serious effort to researching and documenting the contribution this emigre couple made to Canadian visual art.

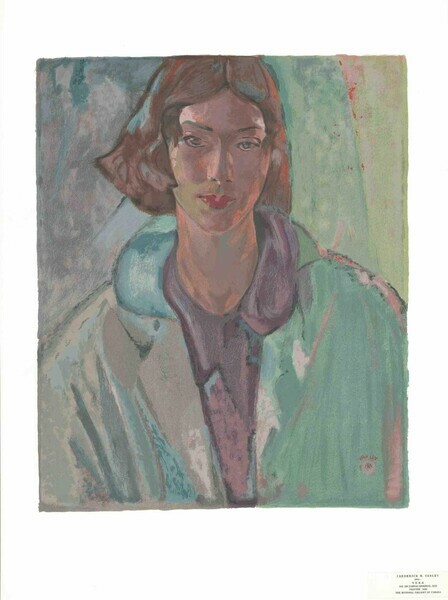

Above, the Markgraph's silkscreen impression of Varley's 'Vera'

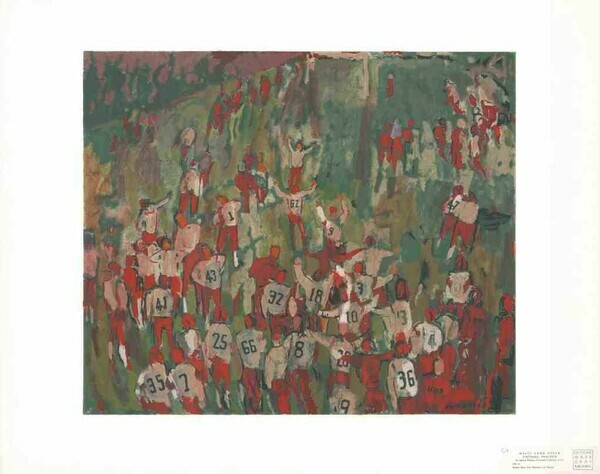

Below, some impressions made of well known Canadian artists of the time and probably produced for sale at The National Gallery of Canada.

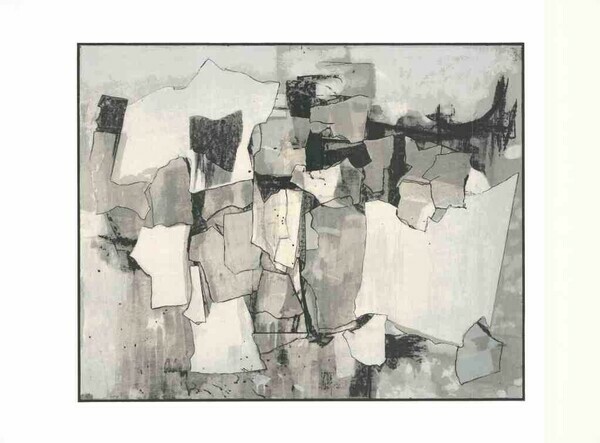

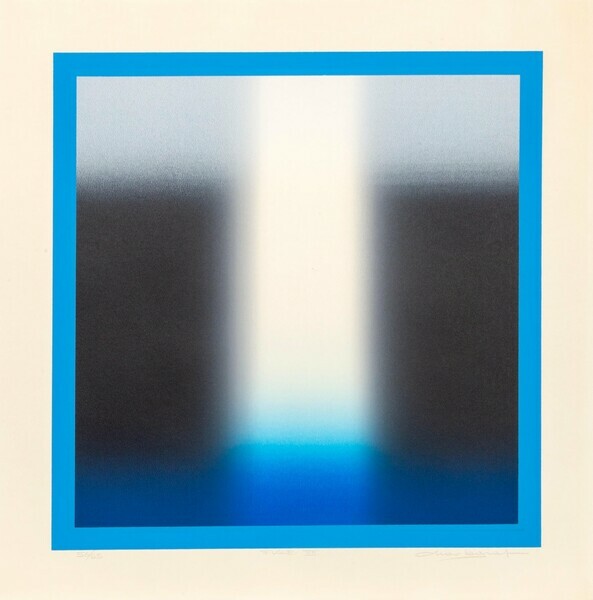

Below, Traudle Markgraf's contribution to a folio of screen prints by the Toronto 20.

Below, some of the Toronto 20's very 'Op' printmaking.

Finally, below, one of the Markgraf's own trademark landscape prints that were highly successful in the late 70's and early 80's. Google searches of the Markgafs will yield results for many more of this series of landscapes being sold at auction.